What does it take for an idea to register? The challenge is that information alone isn’t enough to convince or teach. The way you deliver information matters.

When Melissa Studzinski joined General Mills as a brand manager for the product Hamburger Helper, she got binders of data, market research and surveys, and briefs to help do her job. These “death binders,” as she called them, overwhelmed her with information in the abstract. What clicked for Melissa and her team was when they started visiting moms cooking in their kitchens. She says,

“I’ll never forget one woman, who had a toddler on her hip while she was mixing up dinner on the stove. We know that ‘convenience’ is an important attribute of our product, but it’s a different thing to see the need for convenience firsthand.”

Chip and Dan Heath tell this story in Made to Stick to illustrate the power of concreteness, how decision-making can be easier when guided by specific experiences. For Melissa, actually seeing moms in their homes delivered insights into the value of predictability and convenience for mothers and the kids they were feeding, over the extensive variety the company had been pushing. After simplifying the product line and adapting the ads, sales of Hamburger Helper increased by 11%.

In email marketing, it’s easy to deliver death by confusing abstractions or to take haphazard stabs at what we think will motivate. Instead we can educate, nurture, and convince much more effectively by using concreteness.

How Concrete Language Motivates

Concrete things exist in the real world. You can reach out and touch them, or stub your toe on them, and that vividness provides an entry-point into your audience’s reality. By doing some of the mental work in how your message is presented, people don’t have to expend extra brainpower unpacking fuzzy abstractions and figuring out exactly what you mean.

Whether it’s Aesop’s fables or a punchy elevator pitch, concreteness makes messages easier to understand, remember, and even believe. Concrete language is easier for the brain to parse and recall, and as psychologists Jochim Hansen and Michaele Wänke found in a 2010 study, the mind takes speedily processed and recallable information as more true and believable.

Take this pair of sentences used in the study:

- In Hamburg, one can count the highest number of bridges in Europe. [concrete]

- Hamburg is the European record holder concerning the number of bridges. [abstract]

Even when meaning and level of detail are the same, as in these Hamburg bridge descriptions, subtle linguistic framing makes a meaningful difference in how the information is digested.

“Linguistic concreteness makes the described situations more imaginable,” Hansen and Wänke write. “Increased imaginability, in turn, causes people to believe the statements with greater likelihood.” Framing the information as an experience that the reader is performing instead of plainly stating the fact that Hamburg has the most bridges in Europe feels more concrete, and so, adds credibility and persuasiveness.

Concrete language also paves the way for easier judgment calls and decisions. Because people can imagine and believe concrete statements, they can also envision outcomes and feel more comfortable making decisions towards those outcomes. For instance, researchers found that using more concrete language like “one share of IBM stock” rather than a generic “asset” in disclosures increased investors’ willingness to invest in a firm.

The researchers also found that highlighting concrete language reduces feelings of psychological distance. If you’re not familiar with something, confusing jargon, vague generalities, and abstract ideas end up becoming reasons to lose interest. In email of course, those are immediate reasons to unsubscribe, delete, ignore, or even spam.

Concreteness offers a bridge of believability and affinity to cross over and explore new things.

Applying Concreteness In Your Emails

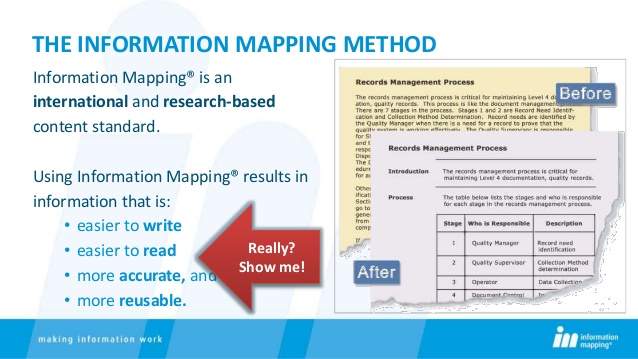

So what does communicating with concreteness mean in practice? Present your message in a way that’s easy to imagine, visualize, and even feel as a reader. That may involve:

- vivid storytelling

- specificity and contextual details

- images, graphics, and photos

- illustrative examples, like testimonials and case study details

- language of the senses

- personas and personalization, speaking to the experiences and needs of specific people (or types of people)

- describing a shared experience, like coming together to solve the same problem

You’re using details, but not just any old details either. They have to be specifics that take into account the audience’s point of view. That way, they can inhabit, imagine, and absorb.

As the Hamburg bridge examples shows, word choice and framing matters too. Here’s a brief primer from psychologists Gün Semin and Klaus Fiedler’s “Linguistic Category Model” which categorizes types of words from concrete to abstract:

- Descriptive action verbs describe specific behaviors in specific situations, with little room for interpretation. They’re less likely to have positive or negative connotations. e.g., count, crouch, kiss, run

- Interpretive action verb describe general behavior in a specific situation and requires some interpretation. These verbs also tend to have positive or negative connotations. e.g., help, cheat, threaten

- State verb describe emotional, mental, or feeling states that have no clear beginning or end. e.g., believe, love, admire, envy

- Adjectives are the most abstract type of word and require a lot of interpretation. e.g., creative, impulsive, reliable

To aim for concreteness, then, use more descriptive and interpretive action verbs and hold off on the adjectives.

Since concreteness helps close gaps with psychological distance, it’s especially useful when you’re dealing with newness — new users or audience members, new features, and other types of new situations. Concreteness, funnily enough, is your welcoming, pillowy soft landing for your readers' minds.

Let’s look at a few email examples:

Close.io

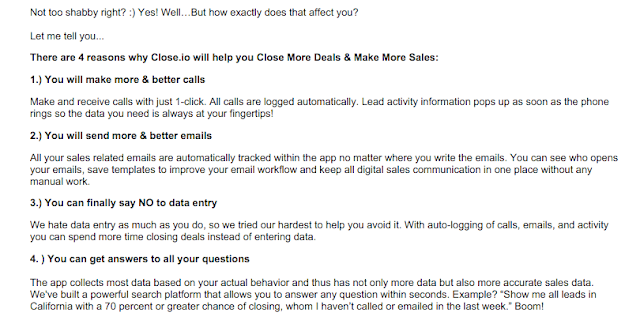

About a week after a new app signup for Close.io, a sales CRM tool, they trigger a very long email from CEO Steli Efti.

Why does this message clock in at over 1,000 words? It’s sharing many stories, all designed to build a bridge to the reader and hopefully ferry them over closer to activation and engagement.

Instead of saying something like “Get started because Close.io is the best!” — Steli shows you why with a resonating origin story. You learn that the Close.io team is solving a pain they had experienced firsthand. That’s why the specific descriptions of existing solutions that turn people into “manual data-entry-monkeys” feels magnetic. They’ve walked in your shoes, their product started out as their own secret sales sauce — this is Close.io’s version of showing that they’ve been in moms’ kitchens and understand their needs.

After testimonial quotes from real-life happy customers, Steli brings the focus back to you. Envision your future — you’ll make better calls and emails, escape the data-entry monkey zoolife, and gain sales data insights — and here are all the details on how that all comes into existence.

Casetext

Casetext is a handy platform for legal writing, research, and publication. Their mission is to make legal knowledge and resources free and understandable. Here’s an email Casetext sent out about one of its contributors Leah Litman, who has written about retroactivity of a law affecting convictions.

The message describes how Leah’s Casetext piece was cited in a legal brief to the Supreme Court, providing a concrete example of the reach and impact that publishing your work on Casetext and being part of its community can have. Your words can go all the way to the top!

Instead of listing out cool, snazzy features or even a bunch of abstract benefits, Casetext succeeds in making all that come together in telling Leah’s story.

The call-to-action button is a great concrete touch, too:

Instead of something generic like “learn more” or “sign up” — it’s a specific and relevant direction: start writing!

Appcues

Appcues, a user onboarding tool, unsurprisingly has put some thought into their triggered activation emails. A few days after you sign up for the product, you get an email with the subject line “Honestly, I was blown away…”

The email highlights one specific company, StoryboardThat, and the specific successes — 112% increase in conversions! — they had using Appcues.

This is a story that will resonate with Appcues’s target audience: here’s a real-life small team that has to deal with many competing priorities but wanted to make their user onboarding more effective. Here is what actually happened after they starting using Appcues, including this impressive A/B test result that blew the customer away.

Their call-to-action button copy is on point too. Even though the link simply takes you into the app, the message is not about signing in or checking Appcues out. Instead, it’s about the very clearly defined goal that the reader has: increase your conversion rate.

Finally, the Appcues team includes the picture of the person featured in the story, which makes it easier to see and understand who was impacted. Aaron is a real person, very much like you, who wants to increase conversion rates without having to wrangle a bunch of code.

Telling relevant stories, showing specific examples, and using concrete language is simply part of good writing and effective communication. Still, concreteness is a remarkably helpful principle that keeps you thinking about your reader and customer’s experience. It battles against your curse of knowledge, the fact that your product or business takes up such a large part of your mind compared to a visitor or prospect, or even loyal customer, and often gets in the way of getting your actual point across.

Our emails and messages shouldn’t be death-by-information but helpful bridges and balloons that bring people up and over to where they want to go.

by Janet Choi