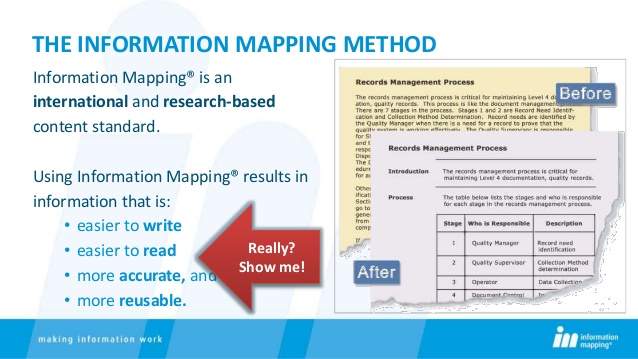

Information mapping is a research-based method for writing clear and user focused information, based on the audience's needs and the purpose of the information. The method is applied primarily to designing and developing business and technical communications. It is used as a content standard within organizations throughout the world.

Overview of the information mapping method

The information mapping method is a research-based methodology used to analyze, organize and present information based on an audience's needs and the purpose of the information. The method applies to all subject matter and media technology. Information mapping has close ties to information visualization, information architecture, graphic design, information design, data analysis, experience design, graphic user interface design, and knowledge management systems.

Components of the method

Information mapping provides a number of tools for analyzing, organizing and presenting information.

Information types

Some of Robert E. Horn's best-known work was his development of the theory of information types. Horn identified six types of information that account for nearly all the content of business and technical communications. The types categorize elements according to their purpose for the audience:

| Information Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Procedure | A set of steps an individual performs to complete a single task |

| Process | A series of events, stages or phases that occurs over time and has a specific outcome |

| Principle | A statement designed to dictate, guide or require behavior |

| Concept | A class or group of things that share a critical set of attributes |

| Structure | A description or depiction of anything that has parts or boundaries |

| Fact | A statement that is assumed to be true |

Research-based principles

The information mapping method proposes six principles for organizing information so that it is easy to access, understand, and remember:

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Chunking | Break up information into small, manageable units |

| Relevance | Limit each unit of information to a single topic |

| Labeling | Label each unit of information in a way that identifies its contents |

| Consistency | Be consistent in use of terminology as well as in organizing, formatting and sequencing information |

| Accessible detail | Organize and structure information so those who need detail can access it easily, while those who don't can easily skip it |

| Integrated graphics | Use graphics within the text to clarify, emphasize and add dimension |

Units of information

Documents written according to information mapping have a modular structure. They consist of clearly outlined information units (maps and blocks) that take into account how much information a reader is able to assimilate.

There is an essential difference between an information unit and the traditional text paragraph. A block is limited to a single topic and consists of a single type of information. Blocks are grouped into maps, and each map consists only of relevant blocks. The hierarchical approach to structuring information greatly facilitates electronic control of content via content management systems and knowledge management systems.

Advantages of information mapping

The information mapping method offers advantages to writers and readers, as well as to an entire organization.

Advantages for writers

Information mapping offers these advantages for writers:

- An easily learned systematic approach to the task of writing that once learned, enables writers to minimize down time and start writing immediately

- A subject-matter independent approach that can be applied to all business-related or technical content

- A content standard that greatly facilitates team writing and management of writing projects

- Enhanced writer productivity, with less time required for both draft development and review, and

- Easy updating and revision of content throughout its life cycle

Advantages for readers

Information mapping offers these advantages for readers:

- Quick, easy access to information at the right level of detail, even for diverse audiences

- Improved comprehension

- Fewer errors and misunderstandings

- Fewer questions for supervisors, and

- Shorter training cycles, less need for re-training

Advantages for organizations

Also an entire organization can benefit from using a content standard like information mapping if the method is used with the following objectives in mind:

Revenue growth by reducing time to create content and accelerating time to market

- Cost reduction by capturing employee knowledge, increasing operational efficiency, reducing support calls, and decreasing translation costs

- Risk mitigation by increasing safety and compliance

History[edit]

Information mapping was developed in the late 20th century by Robert E. Horn, a researcher in the cognitive and behavioral sciences. Horn was interested in visual presentation of information to improve accessibility, comprehension and performance. Horn's development of the information mapping method has won him recognition from the International Society for Performance Improvement and the Association for Computing Machinery.

Review of research

Many independent studies have confirmed that applying the information mapping method to business and technical communications results in quicker, easier access to information, improved comprehension and enhanced performance. It also facilitates repurposing for publication in different formats.[citation needed]

Doubts have been raised over the strength of the research Horn uses to justify some of his principles. For instance, his chunking principle requires lists, paragraphs, sub-sections and sections in a document to contain no more than 7±2 chunks of information.[1] Horn does not state where he got this principle, but an Information Mapping website stated that the principle is "based on George A. Miller's 1956 research".[2] Miller did write a paper in 1956 called "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information", but its relevance to writing is tenuous.[3] Miller himself said that his research had nothing to do with writing.[4] Insisting that lists, paragraphs, sub-sections and sections throughout a document contain no more than 7±2 chunks of information paradoxically assumes that the size of what is not read in a document can influence a reader's ability to comprehend what they do read.[3]

References[edit]

- ^ R.E. Horn, Developing Procedures, Policies & Documentation, Info-Map, Waltham, 1992, page 3-A-2.

- ^ "Mapping FAQs". Infomap.com. Archived from the original on 2010-02-18. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ^ a b Geofrey Marnell, Essays on Technical Writing, Burdock Books, Brighton, 2016, pp. 111–155).

- ^ See http://members.shaw.ca/philip.sharman/miller.txt, Viewed 14 January 2011.

Further reading[edit]

- Robert E. Horn. Mapping Hypertext: The Analysis, Organization, and Display of Knowledge for the Next Generation of On-Line Text and Graphics. ISBN 0-9625565-0-5

- Robert E. Horn. How High Can it Fly? Examining the Evidence on Information Mapping's Method of High-Performance Communication. Note: This publication is available for download on Horn's website: Chapter One and Chapter Two.

Information Mapping is a documentation methodology, developed by Robert E. Horn in 1972. Documents developed according to the Information Mapping methodology have an instantly-recognizable visual style. This is probably because most authors (or organizations) adopting the methodology focus on the style of the Information Mapping documentation itself, copying the style used by Information Mapping Inc. for their own documentation on Information Mapping. However, Information Mapping really stipulates the structure of the information, rather than the visual display of it. It is perfectly possible to adhere to the methodology but use a visual style that is markedly different to what is commonly thought of as 'Information Mapping documentation'.

Information Mapping is built on seven key principles. These are:

- Chunking;

- Relevance;

- Labeling;

- Consistency;

- Integrated graphics;

- Accessible detail;

- Hierarchy of chunking and labeling.

Chunking

The methodology states that:

"Writers should group information into small, manageable units."

Information Mapping defines a 'manageable unit' as "no more than nine pieces of information", which is based on the oft-quoted 'seven-plus-or-minus-two' rule. Information Mapping dictates that this should apply to all levels of documentation - so a manual should have no more than nine chapters, and a bulleted list should have no more than nine list items. However, as discussed in Writing user instructions, this is not always practicable or necessarily desirable. That said, this principle - that information should be grouped into small, manageable units - is good advice from a comprehension perspective.

Relevance

The methodology states that:

"Writers should make sure that all information in one chunk relates to one main point based on that information's purpose or function for the reader."

Put simply, this rule states that a block of information should contain only one type of information. This means that you should not mix (for example) instructions with descriptions. Obviously both of these types of information are permissible (and often necessary) within the same publication. Information Mapping just states that they should be in separate 'blocks' within the document. So you may have a section called "How the XYZ works" and another called "Replacing the widget on the XYZ".

Labeling

The methodology states that:

"After organizing related sentences into manageable unit, writers should provide a label for each unit of information."

This rule states that each 'chunk' of information should have a 'label'. Many proponents of Information Mapping think that this label should appear (traditionally) on the left of the block of information, and word-wrapped within the label column. However, this is not strictly necessary. It is perfectly valid for the label to appear as a 'normal' heading that stretches into the 'content' column. In this context, 'labeling' is best interpreted as providing adequate headings, although headings will typically appear much more often in documents developed according to the Information Mapping methodology than in 'regular' documents.

Examples:

1. 'Traditional' Information Mapping block:

Company policy for system Userids

All users are required to keep their password secret. Users must change their password the first time they log onto the system, and then once a month thereafter. If a user does not change their password for 35 days, they will be prompted to do so by the sytem when they attempt to log on.

2. Adapted Information Mapping block:

Company policy for system Userids All users are required to keep their password secret. Users must change their password the first time they log onto the system, and then once a month thereafter. If a user does not change their password for 35 days, they will be prompted to do so by the sytem when they attempt to log on.

The important thing to remember is that labels must stand out from the text, to allow quick scanning (navigation via the labels). For this reason, it is recommended that the 'content' is always significantly indented (as shown in Example 2 above).

Consistency

The methodology states that:

"For similar subject matters, writers should use similar words, labels, formats, organizations, and sequences."

Consistency should be adhered to on two levels:

- Consistency in language;

- Consistency in format and structure.

Consistency in the language used within a document and across multiple documents within the same documentation set is important, as readers will rapidly become accustomed to the language used and will not have to 'decipher' the text. That is, they will not have to think about the meaning of a word, but will know intuitively (based on their earlier intraction wih this word) what is meant. If you use different words or phrases for the same thing, the user will be required (perhaps subconsciously) to decide each time whether this actually is the same thing as was referred to previously, or is something different. This will increase the time it takes them to assimilate the information.

Consistency in the format and structure of a document is also important. Within a single document, headings should be used consistently. This includes using the same size and typeface for headings at the same level, and also using headings at the same level of granularity. Across documents, consistency can be thought of as providing the same information in the same type of document. For example, if you are developing a suite of user procedures, then every user procedure document should contain the same information, at the same point in the document, and using the same headings and labels.

Integrated graphics

The methodology states that:

"Writers should use diagrams, tables, puictures, etc. as an integral part of the text, not as an afterthought added on when the writing is complete."

This simply means that graphics should be included wherever they are useful. This rule was probably included as a reaction to the prepondency for text-only documents. Integrating graphics typically gives a document a 'lighter' (less-dense) feel, and therefore facilitates comprehension. There are also times when a picture can show instantly what it would take several paragraphs of text to explain.

However, graphics in technical communications must always be functional. The Information Mapping documentation states that "approximately 50 percent of the adult population learns better from pictures and other graphics than from words", but this means that approximately 50% learn better from text! Therefore, graphics should always be in support of the text, and not as an alternative to it.

Note that Information Mapping considers tables to be 'graphics' as well - which explains their extensive use in Information Mapping. However, given that most tables contain text only, it is better to exclude tables from the definition. This allows you to better focus on 'real' graphics (including photos, technical illustrations, and charts and graphs) and identify opportunities for including these in a document.

Accessible detail

The methodology states that:

"Writers should write at a level of detail that makes the information the reader needs readily accessible, and makes the document usable for all readers. In other words, put what the reader needs where the reader needs it. Include clearly labeled overviews, reviews, descriptions, diagrams, and examples for all "abstract" presentations. Place the diagrams, and examples close tothe text they illustrate."

This principle can best be interpreted as simply providing information to a level of detail that is useful to the readers, and then making sure that the readers can easily-locate the relevant detail.

For example, in a set of maintenance instructions, saying simply "Remove the spigot shaft" may not be sufficient. Perhaps the reader does not know how to do this. Consider providing instructions explaining exactly how to remove it. Perhaps the reader is even unfamiliar with exactly what a spigot shaft is, and where it is located. So provide a diagram of one, and/or a photograph of a spigot shaft in-situ. Then clearly label each element - the instructions, the diagram and the photograph - so that users can directly locate them and understand what the element is showing.

Hierarchy of chunking and labeling

The methodology states that:

"Writers should organize small, relevant units of information into a hierarchy, and provide the larger group(s) they have created with a label(s)."

At its simplest, this rule simply means that:

- A document should have a title (label in Information Mapping terminology);

- The document should be split into sections (maps);

- Each section should have a title (label);

- Each section should be split into units of information (blocks);

- Each unit of information should have a title (label).

Some authors struggle with Information Mapping, thinking that there are only three levels within this hierarchy: document, map, and block. This assumption is largely borne out of using the Information Mapping documents as an example, and using the Information Mapping templates which indeed only include these three levels.

However, if you consider this rule in conjunction with the 'chunking' rule, it effectively supports as many levels of the hierarchy as is necessary - as long as each node in the hierarchy has no more than nine sub-nodes.

It is also often assumed that heading numbers are 'no allowed', but again, this is a fallacy. In a three-level hierarchy, where the document is the highest level, and there are no more than 9 nodes at each level, there is not really a need for section numbers. However, once additional levels are inroduced, or the number of nodes is increased, heading numbers - and specifically hierarchical heading numbers (1, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2, 2.1....) can greatly aid navigation. Information Mapping does not explicitly forbid them, so they can be used where it helps.

Example:

1. Controls on system access

1.1 System userids

Each user will be granted a unique password-protected userid which will allow them access to all (and only) functions required to perform their job. Userids must not be shared with other users, under any circumstances.

1.2 System passwords All users are required to keep their password secret. Users must change their password the first time they log onto the system, and then once a month thereafter. If a user does not change their password for 35 days, they will be prompted to do so by the system when they attempt to log on.

2. Controls on physical access to buildings

2.1 Card key

etc.