суббота, 26 июля 2025 г.

понедельник, 31 октября 2022 г.

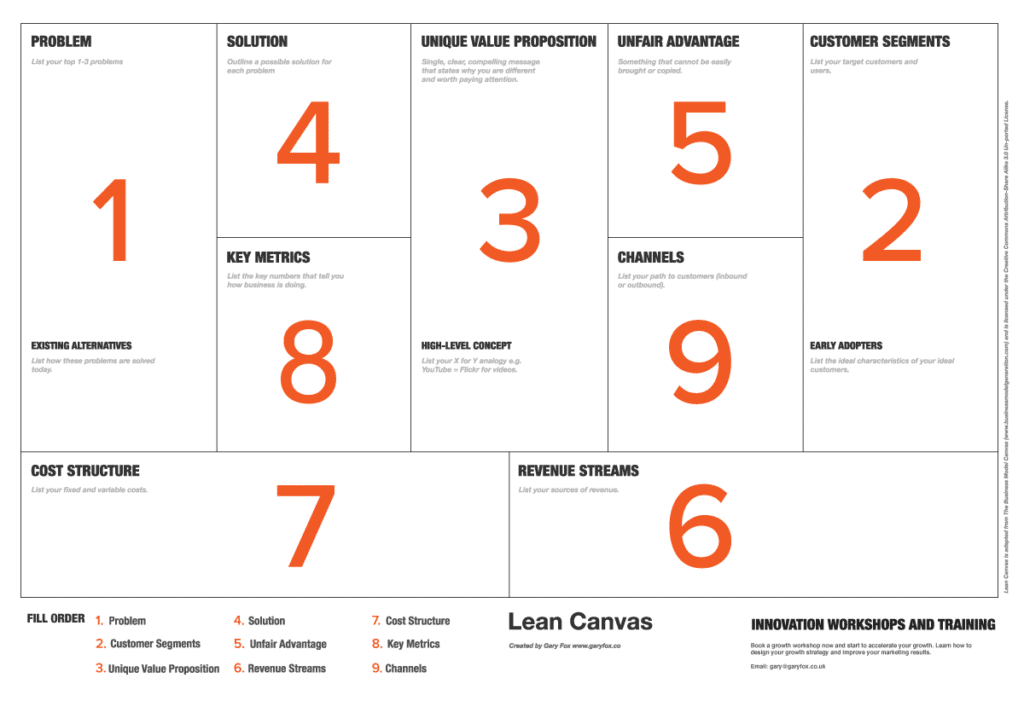

6 – Lean

What is a Lean Canvas?

Lean Canvas is a 1-page business plan template created by Ash Maurya that helps you deconstruct your idea into its key assumptions. It is adapted from Alex Osterwalder's Business Model Canvas and optimized for Lean Startups. It replaces elaborate business plans with a single page business model.

- Fast

- Compared to writing a business plan which can take several weeks or months, you can outline multiple possible business models on a canvas in one afternoon.

- Portable

- A single page business model is much easier to share with others which means it will be read by more people and also more frequently updated.

- Concise

- Lean Canvas forces you to distill the essence of your product. You have 30 seconds to grab the attention of an investor over a metaphorical elevator ride, and 8 seconds to grab the attention of a customer on your landing page.

- Effective

- Whether you're pitching investors or giving an update to your team or board, our built-in presenter tools allow you to effectively document and communicate your progress.

What is the Right Fill Order for a Lean Canvas?

A question I get a lot is: Why isn’t the Lean Canvas laid out more logically? Anyone that has attempted to fill one can relate. You have to jump around from box to box in a seemingly random order.

The main reason for this particular layout was legacy. Lean Canvas was derived from the Business Model Canvas. And instead of changing the canvas layout, I chose to adopt a self-imposed design constraint: Every time I added a new box (like Problem), I’d remove an old box (like Key Partners).

To compensate for usability, I published a suggested fill order in my first book: Running Lean.

Over the years, however, I found myself tweaking this fill order for better flow. While starting with customers and problems was always the common thread, the ordering of the other boxes changed ever so slightly.

The original question then morphed into: Why is there a different suggested fill order across your books and the online app? Which is the right order?

After years of coaching and reviewing of thousands of Lean Canvases, I have finally uncovered the right fill order and I’m ready to reveal it.

Are you ready? Wait for it…

There is none.

Good ideas can come from anywhere

I made a short list of idea sources recently:

1. Scratch your own itch

2. R&D/Invention

3. Analogs

4. Accidental discovery

5. Customer requests

6. External changes

7. Growth Directive

8. Exploit an Unfair Advantage

9. Innovation Theory

As you can see from this list, ideas (yes, even good ones) can come from anywhere. The best way to find a good idea is to have lots of them.

Idea generation doesn’t have to start with customers and problems.

The real challenge, however, isn’t with idea generation, but idea validation.

While idea generation shouldn’t be constrained with a fill order, there is an optimal ideal validation order.

An effective validation plan prioritizes the testing of your riskiest assumptions first. How do you uncover your riskiest assumptions? This is where a Lean Canvas, properly used, can help.

Ideas are jigsaw puzzles

As with jigsaw puzzles, ideas can have many different starting points. Irrespective of where you start though, you still need to end up with a picture that comes together (business model story).

The goal of sketching a Lean Canvas is deconstructing an idea so that you see it more clearly. While imposing a starting point (like customer and problems) was well-intentioned (because they tend to the riskier boxes), I found that too many people would often fake these boxes anyway. They would write problem statements to justify a solution that they already wanted to build. And, in the process, gave themselves a false sense of comfort.

When you’ve already decided to build a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

Yes, this is the Innovator’s Bias. The most amazing part is that people don’t even realize they are doing this. So now I take a different approach.

Before you can confront your Innovator’s Bias, you have to be able to see it.

Instead of imposing a specific order, I now direct people to fill out their canvas by starting with their idea backstory. These triggers reveal a lot about the situation, context, biases, and pitfalls that often also come along for the ride.

Here’s how I do this:

How to Deconstruct an Idea

1. Take a quick snapshot of an idea

The goal of a first Lean canvas isn’t achieving perfection, but taking a snapshot. I recommend setting a timer for 20 minutes and filling out as many boxes as you can within that time limit. It’s okay to leave boxes blank.

Start with your idea backstory. Even though your idea may have felt like a flash of inspiration, ideas can always be traced back to one or more specific events or triggers that caused you to take action.

The Uber founders, for instance, supposedly got the idea after they were unable to find a taxi after an event in Paris. They encountered a problem and decided to do something about it (scratch your own itch). If I were sketching that canvas, I’d start with the problem box.

If you’re a researcher with a discovery or invention that you’re commercializing, you’re starting with the solution box. Might as well make that explicit on the Lean Canvas.

If you’re being asked to find a new market revenue stream by management, make that your explicit starting constraint.

If you want to give it a go, you can get started with a blank Lean Canvas template at http://leancanvas.com.

2. Study your chain of beliefs

What were the first three boxes you filled? Where you start is quite telling.

Filling out a Lean Canvas is essentially stacking a chain of beliefs that build on each other. The early links in the chain constrain and shape your idea. Also, any faulty or weak assumptions early in the chain have a ripple effect. This is why it’s particularly insightful to introspectively study and be critical of the early links in your chain of beliefs — your idea backstory.

What’s interesting to note here is that the seemingly random order of the Lean Canvas is actually a gift in disguise. Had the Lean Canvas been organized more logically, people might be led to fill it in that order and miss following their own more natural thinking order.

Not surprisingly, the solution box often makes the top starting point for most ideas. Next in line are probably revenue/growth directives and exploiting a preexisting unfair advantage.

As you work through your chain of beliefs, categorize each one into on these buckets:

- a leap of faith (gut instinct),

- an anecdotal observation, or

- a fact (based on empirical data).

This will help you take stock of just how grounded your idea is currently.

3. Reorder your chain of beliefs

The point of this exercise isn’t to fault your idea generation method. Remember that “good ideas” can come from anywhere. But how you act on your idea is a much greater determinant of success, than the source of the idea itself.

For an idea to be successful, it needs to simultaneously address three types of risks: customer risk, market risk, and technical risk. We can also show this as the intersection of IDEO’s three circles:

Make sure the starting links in your chain cover all three risks and that they are ideally grounded in factual data. If not, you know what to do next. Get some answers by running some learning experiments.

The Universal Starting Point

For most products, feasibility isn’t what’s riskiest but desirability, then viability. In other words, getting your customer’s attention is the first battle — more so today, than ever before.

To help you home in on your desirability story, I created a Lean(er) Canvas which lets you focus on this almost universal starting risk. https://bit.ly/3WjIVlZ

Reorder your Chain of Beliefs with a leaner Lean Canvas

In my last post, I described how sketching an idea on a Lean Canvas is akin to stacking a chain of beliefs. Later links rely on earlier links, and cracks in your early links have a ripple effect. This is why it’s particularly important to confront your chain of belief and focus on your weakest links first — your riskiest assumptions.

The real challenge isn’t idea generation, but idea validation.

For an idea to be successful, it needs to constantly balance three types of risks: customer risk, market risk, and technical risk and I described the sweet spot of an idea being at the intersection of desirability, viability, and feasibility.

But tackling all three risks at once can be overwhelming. How far do you go on each one and where do you start?

Meet the Lean(er) Canvas

While sketching out a complete Lean Canvas is a great exercise for baselining an idea and internalizing the “business model as the product” mindset, at the earliest stages, however, it helps to more narrowly focus attention on just the two outer boxes of the canvas: Customer segment and Problem.

If you get these assumptions wrong, it’s easy to see how everything else in your business model falls apart. You end up describing a solution that no one wants (not desirable). Even if you manage to build this solution (feasible), no one buys it (not viable). Your channels and unfair advantages don’t offer any respite. Your business model is doomed.

You can also use this customer/problem quadrant to test your desirability, viability, and feasibility risks.

Desirability

Grabbing your customer’s attention with a compelling unique value proposition (UVP) is the first battle. A good UVP is narrow (targets early adopters) and specific (nails a problem).

If you can describe your customer’s problems better than they can, there is an automatic transfer of expertise — your customers start believing that you must also have the right solution for them.

You’ve probably experienced this at your doctor’s office. After receiving a successful diagnosis, you probably believed your doctor had figured out your ailment, and you rushed to fill out their prescription — even though your doctor was simply following a systematic process of elimination by unpacking your symptoms (educated guessing). Marketer, Jay Abraham, calls this phenomenon the Strategy of Pre-eminence.

Describing problems better than your customers grants you super-powers.

Viability

The mistake a lot of innovators make is setting their pricing model relative to their solution. This is cost-based pricing and it’s sub-optimal.

Customers don’t care what it costs to build your product, they want to buy a solution to their problems in order to achieve a desirable outcome. It follows then that pricing should be set relative to problems and outcomes — not your solution.

The best initial evidence of viability or monetizable pain is a check being written.

If your customers are currently spending money (or a proxy for money, like time) on solving a problem with an existing alternative, that’s often a good enough proxy signal for a problem worth solving at this stage.

If on the other hand, you can’t list any existing alternatives, that’s a red flag.

Feasibility

What about feasibility? Problems and solutions are two sides of the same coin. Most people start with a solution and then search for problems. But in a world where the biggest risk is building something nobody wants, it’s more effective to reverse this order.

If your customer and problems assumptions are not yet grounded in empirical learning, it’s prudent to first get them in order.

Be Wary of Your Innovator Bias

When refining your customer/problem quadrant, it’s tempting to do so with respect to your envisioned solution by asking:

- Who is the ideal customer (early adopter) for my solution, or

- What specific problems can I solve with my solution?

But notice that there is no solution box in this quadrant.

This is by design.

Like a prosecutor in court, you need to be able to make the case for the problems listed in this quadrant without relying on your solution. How do you that? By describing problems with respect to your customer’s existing alternatives instead. This is the essence of the Innovator’s Gift — my new project focused on finding better problem discovery techniques. Check it out here.

In other words, don’t focus on problems you can solve with your solution. Rather focus on problems your customers encounter when using existing alternatives. Anchoring your unique value proposition, pricing, and solution against these problems is the secret to crafting an effective UVP that grabs attention and causes a switch — because it’s specific, familiar, and compelling.

This subtle change in perspective is often the difference between inventing fake problems to justify your solution, and uncovering real problems worth solving.

Want to give it a go?

You can create a Lean(er) Canvas at LeanCanvas.com.

And remember:

Make your case for problems without relying on your solution.

понедельник, 15 августа 2022 г.

Lean Canvas Business Model – How To Create A Lean Startup Business

The Lean Canvas Business Model is a variation of the original “business model canvas” devised by Alexander Osterwalder (thanks to its Creative Commons BY-SA license).

Extremely simple in its design, the Business Model Canvas empowers entrepreneurs to create, visualize and test business models without wasting capital or overcomplicating their approach.

Today, it’s used by startups to break new ground, as well as massive companies like GE, P&G and 3M to explore new models and keep up with the competition.

It’s also the core of the book Business Model Generation (co-authored by Osterwalder and Pigneur), which has sold over a million copies in 30 languages.

Harness the power of the Lean Canvas if you are a startup or a new corporate venture.

THE ORIGINAL BUSINESS MODEL CANVAS

It’s said that no business plan survives its first contact with customers

– Osterwalder.

The Business Model Canvas was partially born out of this need to create more flexible plans that could be tested and changed quickly to meet customer needs.

Most importantly, it standardizes the elements of business models and turns them into modules that predictably interact with and influence one another.

The Business Model Canvas is constructed out of nine building blocks? nine blocks that equip you to think of thousands of possibilities and alternatives (and find the best ones):

- Customer segments (your audiences).

- Value propositions (the product or service you provide).

- Channels to reach customers (distribution, stores).

- The type of relationships you want to establish with your customers.

- Revenue streams you generate the key resources you have to work with (capital, talent).

- The key activities you can use to create value (marketing, engineering).

- Your key partnerships (who can help you leverage your model).

- The cost structure of the business model (what you must invest).

These nine elements are arranged to show how they impact each other.

THE LEAN CANVAS BUSINESS MODEL

There are several variations, but the Lean Canvas has gained traction thanks to the lean startup movement. The Lean Startup was made popular by the book written by Eric Ries, if you haven’t read it I do recommend it, it outlines the philosophy and methods used.

Each tool adopts takes a different approach to the original by Osterwalder based on the to the goal or the development stage of the business idea.

One of the most popular of these alternative versions is the “lean canvas” created by Ash Maurya. I’m going to walk you through how it differs from the original and show you when and how to use it.

Lean Canvas Vs Business Model Canvas

The difference between both tools lies in the alteration of the four units:

- Key Partners (Business Model Canvas) vs. Problem (Lean Canvas)

- Key Activities (Business Model Canvas) vs. Solution (Lean Canvas)

- Key Resources (Business Model Canvas) vs. Key Metrics (Lean Canvas)

- Customer Relationships (Business Model Canvas) vs. Unfair Advantage (Lean Canvas)

Who Should Use The Lean Canvas?

The Lean Canvas is designed specifically for startups; it focuses on addressing how your solution solves customer problems and what unique value you offer compared to others in the market or other possible solutions.

It fundamentally challenges you to move away from the idea that you love! and start to validate it.

On the other hand, the business model canvas was created to solve the issue of business plans being uninterruptedly outdated as soon as they are in the initial stages of development. The business model is based on assessing and strategically analyzing an existing business – both internally and competitors.

For that reason, it can be said that it was developed for existing companies, large or small, which already have established their presence in the market and got traction with customers.

However, startups don’t have a customer base and often no products or prototypes. So when they try and use the business model canvas, they aren’t able to fill all the boxes and the canvas remained incomplete.

The Lean Canvas includes also helps deal with uncertainty and risk. All startups are limited by time and resources. They urgently need to reduce risk and prove that their idea fits the market and customers will pay money for it. Of course, the hope is that then it can do this profitably.

The Lean Canvas also reflects the principles of the “Lean Startup? approach build-measure-learn.

In other words, an iterative and rapid cycle of development, testing and validating each hypothesis upon which your idea is based.

| Canvas | Business Model Canvas | Lean Canvas |

| Suitable for | Existing Business | Startups |

| For use by | Senior Management, Operations, Marketing | Entrepreneurs, Founders, Investors |

| Basis | Value proposition, incremental and radical innovation | Idea testing, Evaluation of assumptions, Customers Focus, Value Proposition |

| Application | Mixed teams to develop a common strategic understanding of the existing business model and identify opportunities. | Focus on problem-solution market-fit for new entrants. |

Strengths And Weaknesses Of Lean Canvas

Strengths

- Focus on the problem-solution fit.

- Includes measuring the success.

- Reflects a lean startup mindset: build-measure-learn.

- Unfair advantage helps to differentiate in the market.

- Easy to understand the elements and the structure.

Weaknesses

- Partners and value exchange between different actors is not visible.

- Defining the unfair advantage can set barriers during the early stages of an idea.

- No team or cultural aspects (only within resources).

- Missing building blocks for special usage, such as sustainable business models.

LEAN CANVAS MODEL GUIDE

Having the Lean Canvas as a visual guide made this part “communicating the model/idea” so much more effective — and I think the most valuable function of the tool. Whether you are developing a business idea on your own or as part of a team, the Lean Canvas model can help you visualise each element and challenge if it is right and fits with the other pieces.

The Lean methodology was born out of process improvement with the philosophy of eliminating waste — this includes time, processes, inventory and more. The Lean Canvas, unlike, the Business Model Canvas, is designed specifically for startups.

The problem with business plans for startups & entrepreneurs is that they’re a waste of time. Don’t get me wrong-a well-researched business plan is important but only at the right stage of your business. You still need to understand the plan of how and when you will implement your Lean Canvas.

How Do I Get Started?

The Lean Canvas uses 9 blocks suited to the needs/ purposes/requirements of a Lean Startup. The Lean Canvas is a perfect one-page format for iterating ideas and challenging assumptions. Building the business model that then looks like its a viable and sustainable business.

The blocks guide you through logical steps starting with your customer problems right through to your unfair advantage (often the hardest block to answer).

Start by the printing of several canvases and then using these to build out your idea. I’ve made some very large canvas pdf’s that are ideal for printing and then using post-it notes.

Different Ways Of Using The Lean Canvas.

One of the important things I always recommend is to keep different versions as you progress with your business model. You might find that you revert back to some ideas as you go through the process. Also, it is a good way of seeing your own progress in your ideas.

If you are using a large print out with post-it notes then simply take photos at different stages so you have a digital record of the evolution.

1. From Initial Idea to Business Launch. The Lean Canvas allows you to map out the key foundations of your startup. It prompts you to analyze and prioritize your goals during the early stages of your business. From the problem to key metrics, the Lean Business Model helps you build the logic that will help your business foundations be stronger.

2. Market and Competitor Analysis. The Lean Startup Canvas can also help you to identify your advantages over other market competitors. As part of developing your business model canvas you should compare the dominant players in the market and their model. It also generates a blueprint for your startup to identify a consumer segment based on your solutions.

3. Launch and Growth. A good practice and part of testing and pivoting in a startup are to revisit the lean canvas. As their company evolves, you can maintain the focus of real-life operations on your unique value proposition.

Step 1 (Of 10): Problem.

Each customer segment (CS) you identify will have a set of problems that need solving. In this box try listing one to three high priority problems that each customer segment has. Without a problem to solve, you don’t have a product/service to offer.

Problems can be based on complexity, time vs. ease of use, price, and quality vs. features, there are many different ways to identify problems. If you’re not sure then take time to go out and talk to customers. Also, observe them in the situation and context that relates to your idea.

Step 2 (Of 10): Customer Segments.

From practice, it is often better to focus on one set of customers to start with. For example, engineers are an identifiable segment. However, you need to get into the detail of what type of engineers and build out a persona for them. The Problem and Customer Segment boxes are intrinsically linked, i.e. You can’t think of any problems without a Customer Segment, and vice versa.

Use the Persona Canvas to really identify you’re customer segment. All too often the reason startups fail or need to pivot rapidly is because they didn’t spend enough time understanding the customer segment upon which the rest of the business model depends. Without customers, there is no business.

Step 3 (Of 10): Unique Value Proposition.

The Unique Value Proposition is situated in the middle of the Lean Canvas. A promise of value to be delivered to the customers is called a value proposition. This should be the main reason a potential customer wants to buy from you. Thinking and understanding why your product is useful to your Customer Segments and why they want to buy is the best way to understand your Unique Value Proposition.

Research your competition using multiple methods. Ask target customers about other products or services they’ve explored or used. Utilize search engines, social media and trade publications to become an authority on your industry.

The danger is to create a value proposition, and product for that matter, that is not different from the competition. Be careful to understand how your value proposition stacks up against potential competitors.

A UVP should:

- Be easy to understand in about five seconds.

- Communicate the benefit a customer receives from using your products and/or services.

- Explain how your offering is different from and better than competitors’.

Identify ‘REAL’ Pain Points

Put yourself in your customers’ shoes and describe up to 3 problems they face. Try to understand their unique needs and challenges. These problems will lead to working business models.

Be Careful! Identifying the wrong problem is a problem. For instance, you might believe your SaaS platform is struggling because your logo and copy aren’t engaging, but the real issue might be that users don’t understand why they need your product. If you skip this step, you risk wasting time and energy on non-existent problems.

There are several ways you can get a more informed understanding of your problems, including:

- User Interviews

- User Tests

- Surveys and Questionnaires

- Ethnography – observing customers

Step 4 (Of 10): Solution.

Finding a solution to the problem is the goal of your startup! What you need to do is Get Out The Building — a phrase coined by the godfather of Lean Startup, Steve Blanks. And what Blank’s here is that the solution is not in your office, it’s out there in the streets. So go interview your customer segment, ask them questions, and take those learnings. Remember the Lean Startup is validated learning through a continual Build — Measure — Learn cycle.

Careful! You might think you know the best part of your product or service, but completing the previous sections of the Lean Canvas may prove otherwise. Your users will ultimately determine which aspects of your product they’re most eager to use and will subsequently find most beneficial.

Run through the main features and benefits of your product or service. Then prioritize them. Then go to a customer and ask them to prioritize them. Consider the strengths and flaws of each and reduce your list down to the top three. You can also use other strategy exercises like using brand positioning to help define your solution.

Step 5 (Of 10): Unfair Advantage.

What will makes you stand out? This is far harder than it seems. Remember that your unfair advantage needs to be sustainable. Ideally, this is something that competitors will be hard to replicate.

What are some resources you possess that can’t be easily copied or acquired by other businesses? Here are some examples of Unfair Advantages to get you thinking about what makes you stand out:

- Inside Information: In-depth knowledge or skills that are critical to the problem domain. Basically, this means able to address the needs of customers in specialized areas better than the competition. The competition might, for instance, have generalists and you have specialists.

- Personal Authority: If you’re a scholar in a specific field, an award-winning builder of a certain product, or an expert on given services, you hold sway over competitors.

- Community: If you have a network of customers and partners at your fingertips, you’re in a good position to make big strides quickly and that can make it hard for others to catch-up.

- Internal Team. Do you have a highly-talented and unique team?

- Reputation. Have you built up a following, a name that people instantly associate with proven success? A proven and popular brand reputation is a major advantage.

- Intellectual Property: Is there a method, technology or some process that you can protect.

Step 6 (Of 10): Revenue Streams.

How you price your business will depend on the business model, e.g. whether you are offering a SaaS a physical product or a combination of services and products.

A common problem is that startups price low. This can pose a few problems. Getting people to sign up for something for free is a lot different than asking them to pay. There is also the idea of perceived value. If you price too low or even start-off free then you run the risk of undervaluing your brand.

The maximum price may render your product unmarketable but the minimum price could seriously hurt the future prospects of your business. First of all, once you start at a low price it is very difficult to raise it without losing customers.

The price model should be thoroughly tried and tested several times. I can assure you that unsuspecting factors will force you to pivot again, and again, and again until you get it right.

Some sources of revenue dependent on your type of business model:

- Asset Sales: Customers pay to purchase ownership of your product, be it a book, camera or coffee mug.

- Usage Fees: Payment for the number of uses of your product such as the number of minutes spent on a phone or nights in a hotel room.

- Subscription Fees: Consumers pay for unlimited usage of a product for a given time period like a monthly gym membership or a yearly newspaper subscription.

- Delivery or Installation Fees: Consumers pay for the installation and/or delivery of your product or service.

- Advertising: Companies pay you to advertise their product or service on your site.

Step 7 (Of 10): Cost Structure.

Try to consider all your costs of doing business. Not only the cost of sales e.g. customer acquisition, but the overall underlying costs across the board.

90% of new businesses fail because they do not properly consider the cost of launching and running their businesses.

To ensure you don’t accidentally overlook a cost, consider how each section of your lean canvas might drive business expenses. For example, what is the cost to launch your product or services? What is the cost to identify target consumers, connect with users, and keep them informed of your brand? When filling in this section, take time to reflect on all possible cost scenarios.

Separate out your variable costs (costs that vary as you scale) to your fixed costs. This way you can get an idea of what costs will increase as you grow.

Step 8 (Of 10): Key Metrics.

If you can’t measure it you can’t manage it – that saying still rings true. Every business owner needs to understand the key levers that are driving performance. These key metrics that are used to monitor daily, weekly and monthly. Moreover, they are the means by which you understand if your product-market-fit. The best way to help with this is to visualize a funnel top-down that flows from the large open top, through multiple stages to the narrow end. A good model to help with this is in the growth marketing canvas – based on AAARRR.

Step 9 (Of 10): Channels.

You will have noticed I have left channels till last. There is a good reason for this. The tendency is that people get caught up in the excitement and creativity of marketing and channels without thinking about the numbers.

How will consumers come into contact with your brand? Where will they first learn about your business? Will it be through social media? If so, which ones? Will it be through paid ads? If so, where will you advertise and how? What are the costs of the ads? You can use the customer mapping template I’ve created to create a strong strategy to help you define what channels are best.

Once you understand your numbers you can start to investigate your channels much more realistically. What can you afford to spend on a cost per acquisition? They are ways to research channels costs and start to develop a growth strategy that works for your new business.

Step 10 (Of 10): Applications, Review & Next Steps.

The Lean Canvas template is not set in stone. Like other tools, it should be revisited and revised to check your fit to the market and your customers. Many companies revisit Lean Business Models when they are considering a new feature or adding a new service.

This helps internal teams understand and hone in on the central customer problem their updates are resolving.

The Lean Startup Summary exercise helps drive focus down to the right feature-set (solution), metrics, and customer segments which in turn aligns sales, marketing, design and development efforts.

https://bit.ly/3QIYK1T