The ability to plausibly forecast the future requires alternating between broad and narrow ways of thinking.

Futurists are skilled at listening to and interpreting signals, which are harbingers of what’s to come. They look for early patterns — pretrends, if you will — as the scattered points on the fringe converge and begin moving toward the mainstream. The fringe is that place where hackers are experimenting, academics are testing their ideas, technologists are building new prototypes, and so on. Futurists know most patterns will come to nothing, so they watch and wait and test the patterns to find those few that will evolve into genuine trends. Each trend is a looking glass into the future, a way to see over time’s horizon. This is the art of forecasting the future: simultaneously recognizing patterns in the present and thinking about how those changes will impact the future so that you can be actively engaged in building what happens next — or at least be less surprised by what others develop. Futures forecasting is a learnable skill, and a process any organization can master.

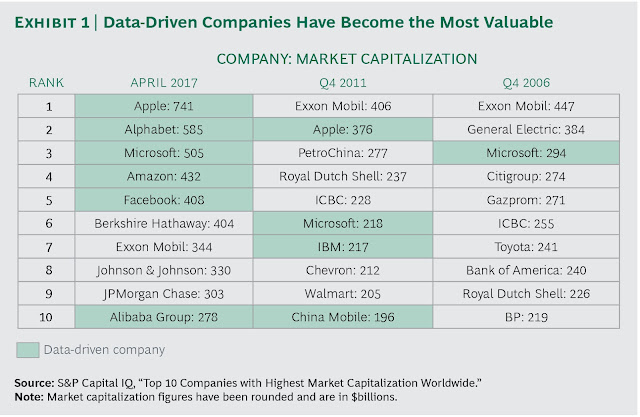

Joseph Voros, a theoretical physicist and senior lecturer in strategic foresight at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia, offers my favorite explanation of futures forecasting, saying it informs strategy making by enhancing the “context within which strategy is developed, planned, and executed.”1 The advantage of forecasting the future in this way is obvious: Organizations that can see trends early can better prepare to take advantage of them. They can also help shape the broader context, with an understanding of how developments in seemingly unconnected industries will affect them. Most organizations that track emerging trends are adept at conversing and collaborating with those in other fields to plan ahead.

Although futures studies is an established academic discipline, few companies employ futurists. That’s starting to change as more leaders become familiar with the work futurists do. Accenture, Ford, Google, IBM, Intel, Samsung, and UNESCO all have had futurists on staff, and their work is quite different from what happens within the traditional research and development (R&D) function.

The futurists at these organizations know that their tools are best used within a group — and that the group’s composition matters tremendously to the outcomes they produce. Here’s why. Within every organization are people whose dominant characteristic is either creativity or logic. If you’ve been on a team that included both groups and didn’t have a great facilitator during your meetings, your team probably clashed. If it was an important project and there were strong personalities representing each side, the creative people felt as though their contributions were being discounted, while the logical thinkers — whose natural talents lie in managing processes, projecting budgets, or mitigating risk — felt undervalued because they weren’t coming up with bold new ideas. Your team undoubtedly had a difficult time staying on track, or worse, you might have spent hours meeting about how to have your next meeting. I call this the “duality dilemma.”

The duality dilemma is responsible for a lack of forward thinking at many organizations. It contributed to the decline of BlackBerry Ltd.’s smartphone business; the company (formerly known as Research in Motion Ltd.) never had an executable plan to remake the phone’s form factor and operating system in the age of the iPhone. Right-brained creatives wanted to make serious changes to the phone, while left-brained process thinkers were fixated on risk and maintaining BlackBerry’s customer base.2 The future of the business hinged on the company’s ability to bring both forces together to forecast trends and plan for the future.

BlackBerry’s experience suggests that forecasting the future of a product, company, or industry should neither be relegated to inventive visionaries nor mapped entirely by left-brain thinkers. Futures forecasting is meant to unite opposing forces, harnessing both wild imagination and pragmatism.

Turning a Dilemma Into a Dynamic

Overcoming the duality dilemma — and getting full use of both your creative- and logic-oriented team members — in order to track emerging trends and forecast the future is possible. But counterintuitively, it’s a matter of highlighting — rather than discouraging or downplaying — the strengths of each side. Stanford University’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (also known as the d.school) teaches a brainstorming technique that addresses the duality dilemma and illuminates how an organization can harness both strengths in equal measure by alternately broadening (“flaring”) and narrowing (“focusing”) its thinking.3

When a team is flaring, it is finding inspiration, making lists of ideas, mapping out new possibilities, getting feedback, and thinking big. When it is focusing, those ideas must be investigated, vetted, and decided upon. Flaring asks questions such as: What if? Who could it be? Why might this matter? What might be the implications of our actions? Focusing asks: Which option is best? What is our next action? How do we move forward?

The forecasting method I have developed — one, of course, influenced by other futurists but different in analysis and scope — is a six-step process that I have refined during the past decade as part of my work at the Future Today Institute. The first four steps involve finding a trend, while the last two steps inform what action you should then take. (See “A Six-Step Forecasting Methodology.”)