Agile project management is an iterative approach to delivering a project throughout its life cycle.

Iterative or agile life cycles are composed of several iterations or incremental steps towards the completion of a project. Iterative approaches are frequently used in software development projects to promote velocity and adaptability since the benefit of iteration is that you can adjust as you go along rather than following a linear path. One of the aims of an agile or iterative approach is to release benefits throughout the process rather than only at the end. At the core, agile projects should exhibit central values and behaviours of trust, flexibility, empowerment and collaboration.

Why do you need agile in project management?

Agile is a philosophy that concentrates on empowered people and their interactions and early and constant delivery of value into an enterprise. Agile has enduring appeal and ‘proved’ itself in software development. However, although the arguments are compelling, evidence that it is more beneficial than alternative approaches remains largely anecdotal.

What are the benefits of agile working?

Agile could be a project delivery ‘placebo’; working because those involved want it to. Agile empowers people; builds accountability, encourages diversity of ideas, allows the early release of benefits, and promotes continuous improvement. It allows decisions to be tested and rejected early with feedback loops providing benefits that are not as evident in waterfall.

In addition, it helps deliver change when requirements are uncertain, helps build client and user engagement by focuses on what is most beneficial, changes are incremental improvements which can help support cultural change. Agile can help with decision making as feedback loops help save money, re-invest and realise quick wins.

However...

Agile focuses on small incremental changes and the challenge is that the bigger picture can become lost and create uncertainty amongst stakeholders. Building consensus takes time and challenges many norms and expectations. Resource cost can be higher; co-locating teams or invest in infrastructure for them to work together remotely. The onus can be perceived to shift from the empowered end-user to the empowered project team with a risk that benefits are lost because the project team is focused on the wrong things.

When to adopt an agile approach

A critical governance decision is to select the appropriate approach as part of the project strategy. Level of certainty versus time to market is the balance that needs to be considered when selecting suitable projects to go agile. Organisations have to be realistic: the objective is not agile but good delivery, and a measured assessment of the preferred approach is essential to achieve that goal. This is defined by the project type, its objectives and its environment.

Agile is not a panacea, many practice its principles without knowing. Projects delivering end-user benefits is an agile principle which should also exist using traditional methodologies. Collaborative working will always: improve benefits; speed up delivery, improve quality, satisfy stakeholders and realise efficiencies.

What are the principles of agile working?

Agile is a framework and a working mind-set which helps respond to changing requirements. It focuses on delivering maximum value against business priorities in the time and budget allowed, especially when the drive to deliver is greater than the risk. There are four principles which are typically used to highlight the difference between agile and waterfall (or more traditional) approaches to project management:

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

In an agile environment, how a project is delivered is driven by a team working with end users, focus is on a core deliverable and iterating over time. Allowing the user to drive the design of a project can make a significant difference to project outcomes. Agile favours benefits and innovation through collaboration with a particular focus on customer satisfaction, quality, teamwork and effective management.

Individuals and interaction over process and tools

Agile emphasises a shift from a control to consensus. Focus is on people achieving benefits through engaged, accountable, high performing teams with focus on sharing data, openness, team communication and learning from feedback. This often requires behaviour change; those playing management roles become in and of the team both serving and leading to create commitment and accountability to an end goal.

Responding to change over following a structured plan

The traditional ‘waterfall’ uses an agreed scope to create a time and resources plan. Agile establishes the resources and time which ultimately drive scope. There will be a number of time and cost delivery windows, sprints, through which the project will evolve.

An agile environment establishes a minimum viable product (MVP); the core project deliverable to trigger the start of a delivery. This is likely to change as the project team realises other opportunities or benefits that become available throughout each sprint.

Prototyping/working solutions over comprehensive documentation

The team owns the MVP working together to develop the product; what they will deliver and how they will deliver it. The delivery team is ‘cocooned’ to focus on the solution to the problem they are dealing with. The team will make constant adjustments to the scope of the product.

What are agile methods/ what are agile methodologies

Agile is a family of development methodologies where requirements and solutions are developed iteratively and incrementally throughout the project life cycle. Agile methods integrate planning with execution, allowing an organisation to create a working mindset that helps a team respond effectively to these changing requirements.

Agile does not prescribe one particular way of working. Rather it provides a framework which describes a collection of tools, structure, culture and discipline to enable a project or programme to embrace changes in requirements.

- The agile, or iterative, project promotes collaborative working, especially with the customer. This involves the customer being embedded in the team, providing the team with constant and regular feedback on deliverables and functionality of the end product.

- The best agile approaches are very disciplined and can, and should, be integrated into corporate procedures such as governance.

- An agile project's defining characteristic is that it produces and delivers work in short bursts (or Sprints) of anything up to a few weeks. These are repeated to refine the working deliverable until it meets the client's requirements.

Examples of agile methodologies

There are several methodologies that can be used to manage an agile project; three of the most popular being Kanban, Scrum and Lean.

Where traditional project management will establish a detailed plan and detailed requirements at the start then attempt to follow the plan, agile starts work with a rough idea of what is required and by delivering something in a short period of time, clarifies the requirements as the project progresses.

These frequent iterative processes are a core characteristic of an agile project and, because of this way of working, collaborative relationships are established between stakeholders and the team members delivering the work.

Here are some more agile methodologies:

- DAD (disciplined agile delivery) – a process-decision framework.

- DSDM, or dynamic systems development method – agile development methodology, now changed to the ‘DSDM project management framework’.

- Kanban – a method for managing work, with an emphasis on just-in-time delivery.

- Kanban board – a work and workflow visualisation tool which summarises the status, progress, and issues related to the work.

- Lean – a method of working focused on ‘eliminating waste’ by avoiding anything that does not produce value for the customer.

- LeSS (large-scale Scrum) – agile development method.

- RAD (rapid application development) – agile development method; enables developers to build solutions quickly by talking directly to end users to meet business requirement.

- SAFe (scaled agile framework enterprise) – agile methodology used for software development.

- Scaled agile – agile scaled up to large projects or programmes, for example by having multiple sub-projects, creating tranches of projects, etc.

- Scrum – an agile methodology commonly used in software development, where regular team meetings review progress of a single development phase (or Sprint).

- Scrum of scrums – a technique to operate Scrum at scale, for multiple teams working on the same product.

- XP (eXtreme Programming) – agile development methodology used in software development; allows programmers to decide the scope of deliveries.

Difference between agile and waterfall approaches to project management

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation;

- Individuals and interaction over process and tools;

- Responding to change over following a structured plan;

- Prototyping/working solutions over comprehensive documentation.

There are four principles which are typically used to highlight the difference between agile and waterfall (or more traditional) approaches to project management:

Traditional 'waterfall’ approaches will tend to treat scope as the driver and calculate the consequential time and cost; whereas ‘agile’ commits set resources over limited periods to deliver products that are developed over successive cycles.

Agile and waterfall approaches to project management exist on a continuum of techniques that should be adopted as appropriate to the goals of the project and the organisational culture of the delivery environment.

Overall, agile and waterfall approaches to project management both bring strengths and weaknesses to project delivery, and professionals should adopt a ‘golf-bag’ approach to selecting the right techniques that best suit the project, the project environment and the contracting parties with an emphasis on the behaviours, leadership and governance, rather than methods, that create the best opportunities for successful project delivery.

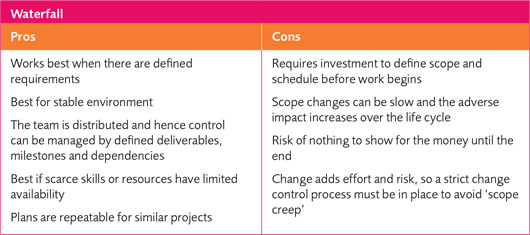

Pros and cons from The Practical Adoption of Agile Methodologies:

Agile project management glossary

Agile terminology can be confusing. We have compiled a list of the most common agile terms you may come across, and their definitions:

- Agile – a project management approach based on delivering requirements iteratively and incrementally throughout the life cycle.

- Agile development – an umbrella term specifically for iterative software development methodologies. Popular methods include Scrum, Lean, DSDM and eXtreme Programming (XP).

- Agile Manifesto – describes the four principles of agile development: 1. Individuals and interactions over processes and tools. 2. Working software over comprehensive documentation. 3. Customer collaboration over contract negotiation. 4. Responding to change over following a plan.

- Backlog – prioritised work still to be completed (see Requirements).

- Burn down chart – used to monitor progress; shows work still to complete (the Backlog) versus total time.

- Cadence – the number of days or weeks in a Sprint or release; the length of the team’s development cycle.

- Ceremonies – meetings, often a daily planning meeting, that identify what has been done, what is to be done and the barriers to success.

- DAD (disciplined agile delivery) – a process-decision framework.

- Daily Scrum – stand-up team meeting. A plan, do, review daily session.

- DevOps (development/operations) – bridges the gap between agile teams and operational delivery to production.

- DSDM (dynamic systems development method) – agile development methodology, now changed to the ‘DSDM project management framework’.

- Kanban – a method for managing work, with an emphasis on just-in-time delivery.

- Kanban board – a work and workflow visualisation tool which summarises the status, progress, and issues related to the work.

- Lean – a method of working focused on ‘eliminating waste’ by avoiding anything that does not produce value for the customer.

- LeSS (large-scale Scrum) – agile development method.

- RAD (rapid application development) – agile development method; enables developers to build solutions quickly by talking directly to end users to meet business requirement.

- Requirements – are written as ‘stories’ that are collated into a prioritised list called the ‘Backlog’.

- SAFe (scaled agile framework enterprise) – agile methodology used for software development.

- Scaled agile – agile scaled up to large projects or programmes, for example by having multiple sub-projects, creating tranches of projects, etc.

- Scrum – agile methodology commonly used in software development, where regular team meetings review progress of a single development phase (or Sprint).

- Scrum of scrums – a technique to operate Scrum at scale, for multiple teams working on the same product.

- Scrum master – the person who oversees the development process and who makes sure everyone adheres to an agreed way of working.

- Sprints – a short development phase within a larger project defined by available time (‘timeboxes’) and resources.

- Sprint retrospective – a review of a Sprint providing lessons learned with the aim of promoting continuous improvement.

- Stories – see Requirements.

- Timeboxes – see Sprints.

- Velocity – a measure of work completed during a single development phase or Sprint.

- Waterfall – a sequential project management approach that seeks to capture detailed requirements upfront; the opposite to agile.

- XP (eXtreme Programming) – agile development methodology used in software development; allows programmers to decide the scope of deliveries.

Interview with Sue Clarke videos

This APM Research Fund study builds on the 2015 APM North West Volunteer study on the practical adoption of agile methodologies which provided a review of approaches at a project level, this study aims to investigate the level of practical adoption of those programme and portfolio components addressed by scaled agile methodologies.

The objective of the study was to understand the extent to which scaled agile tools, techniques and roles are practically in place in corporate portfolio, programme, project and development management methodologies, to determine the level of corporate commitment to exploiting scaled agile, e.g. pilot, full use, selective based on need, as well as drivers for selection or deselection of the framework based on the overheads.

Can agile be scaled?

This APM Research Fund study builds on the 2015 APM North West Volunteer study on the practical adoption of agile methodologies which provided a review of approaches at a project level, this study aims to investigate the level of practical adoption of those programme and portfolio components addressed by Scaled Agile methodologies.

The objective of the study was to understand the extent to which scaled agile tools, techniques and roles are practically in place in corporate portfolio, programme, project and development management methodologies, to determine the level of corporate commitment to exploiting scaled agile, e.g. pilot, full use, selective based on need, as well as drivers for selection or deselection of the framework based on the overheads

Who is the intended audience?

The proposed target audience is APM corporate members and their employees but would also be of interest to individual practitioners, training providers and those who are considering or have adopted Agile and now want to expand its use, or who have been struggling to align timeframes and products across multiple agile deliveries.

Why is it important?

We hope that the findings help to improve the understanding of Scaled Agile adoption, and identify practical steps rather than theory, for members, both corporate and individual, to understand what they may need to consider when adopting any scaled agile methodology.

The findings help provide an overview of the state of the uptake of scaled agile project management in the North West whilst understanding the methods, tools and techniques from project professionals to add to the understanding of good practice.

Who took part in the research?

To avoid concern about gaining approval to publish, even anonymously, potentially sensitive information about project performance, individual project managers, rather than corporates, were approached for interviews.

The research is based on an online survey and interviews with 12 project managers who all had had first-hand experience of leading and delivering agile projects of varying sizes worth on average around £20 million. All participants had recognised agile project management or management qualifications. Only one project manager had used agile for non-IT delivery. All had undertaken some form of formal training or accreditation in at least one scaled agile management approach.

What did we discover?

We hope that the findings help provide a useful overview of the state of the uptake of scaled agile project management in the North West whilst enhancing understanding around the practices, tools and techniques from practitioners to add to the existing understanding of good practice. However, it proved difficult to have a complete interview about agile project management without falling into the discussions around agile development. Consequently, some of the findings relate more to scaled agile development methods in a project/programme context. Therefore, further research questions are indicated into why the adoption of agile project management is still confused with agile development approaches.

Findings included:

- Agile project management and agile development are not necessarily seen as different practices and the terms are used interchangeably.

- Adoption is limited and still largely restricted to use by IT; however, the determining factor is the existing maturity of agile adoption. Agile is still predominantly seen by the majority of study participants as a development approach, rather than a project management framework.

- An agile enterprise portfolio can provide the right environment to gain executive Support

- Most organisations start with a pilot, then decide on whether to simply scale up a team method or go for an enterprise-driven framework when success can be proven.

- Drivers for adoption of scaled agile were determined by the participant programme managers rather than from a corporate appetite and are mainly related to speed to market.

- The mindset is more important than the method, as most techniques are adaptable and transferable.

- HR support for reward mechanisms and multiskilled job profiles is needed to aid new ways of working.

- The change in reporting approach is radical – reporting under the new approach needs careful consideration, explanation and practice

Further research is needed to understand how to scale up team-level agile project management methods.

What were the main challenges?

- Obtaining participating organisations and individuals that provided a good cross section of the UK project profession that enabled handover to be assessed across a range of business sectors. The projects delivered by the participants were, in the main, IT solutions; this could be due to some membership or network bias

- It proved difficult to have a complete interview about agile project management without falling into the discussions around agile development

- https://bit.ly/3sjZ2Sj

What Is Agile Project Management in Business?

- Max Freedman

While adding more steps, the agile project management model can help you provide a more transparent collaborative process.

When working on a project, you can take a variety of approaches to complete it. It is always best to set a course of action from the start. Project managers often turn to specific models when sketching out their plans for completion. Traditional project management models focus on five steps: initiation, planning, execution, monitoring and completion.

Agile project management is another approach. With the agile project management model, there are often far more than five steps, but this doesn't necessarily mean the project will take longer. In fact, your team could complete the project sooner. That's part of the reason why agile project management is becoming common in many industries.

What is agile project management (APM)?

Agile project management is an iterative approach to project management. In the agile method, you complete small steps, known as "iterations," to finish a project. A product of some sort typically follows an iteration, with clients immediately able to give their feedback on these products. As such, in the agile process, you move away from working on large projects for long periods without outside involvement. The goal is to focus on a series of smaller tasks that more deftly meet your long-term goals as well as your clients'.

What is the difference between project management and agile project management?

Whereas the traditional project management and product development process follows a linear path, agile methodology is nonlinear and thus allows for deviance from an ordered set of steps.

APM comprises short tasks that facilitate quicker routes to product development and more frequent, thorough feedback from clients. In turn, teamwork and collaboration become easier, since more feedback on more products is available. [Read related article: Pros and Cons of 7 Project Management Styles]

Who uses agile management?

Agile management is most common in software development and IT. That's because the iterations of an agile software development project result in client feedback along the way, so software developers can adjust small lines of code as a project develops instead of conducting a massive overhaul upon completion. As any developer knows, changes to one line of code can set off a ripple effect of additional changes – a sort of chaos sequence that agile project management helps to avoid.

Of course, agile management isn't solely a software strategy. It's becoming common in several industries prone to uncertainty, such as marketing, automotive manufacturing and even the military. All these industries stand to benefit from a key advantage of the iterative approach: building a solution in real time instead of working toward an inflexible, predefined outcome.

What are the four core values of agile project management?

When implementing APM practices into your company's operations, start by transforming its four core values into the basis of all your workflows. These are the core values, as outlined in the Agile Manifesto:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

Although the second core value mentions software, you can theoretically apply the logic of working parts over thorough documentation to any long-term project. Learning another key component of the Agile Manifesto – its 12 principles – may help you see how.

What are the 12 principles of agile?

These are the 12 principles of agile project management from the Agile Manifesto. (Keep in mind that you can replace the word "software" with whatever product your company sells.)

- "Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software." Some clients may become uneasy when they don't see any finished products or other clear updates after extended periods of work. The early and continuous delivery described in the Agile Manifesto circumvents this issue.

- "Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer's competitive advantage." This way, you work not toward a rigid idea of a solution, but an ever-adapting product that addresses the pain point identified long before the solution was fully clear.

- "Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference for the shorter timescale." With each deliverable you provide to a client, you lessen the chances that you'll need to make massive changes to one part of a project that will have a ripple effect on other parts. You also increase your transparency and ability to collaborate, thus keeping your clients happier.

- "Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project." This principle reminds project teams that those who prioritize business may have different views and needs from those who focus on product research and development. As such, it can be easy to drift away from shared goals without daily collaboration.

- "Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done." Creating a space in which team members have the tools and supervisor support to move through iterations is key to efficiently guiding a project from loose idea to firm final product.

- "The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation." No, you shouldn't entirely forgo email, phone, and digital communication, but real-time conversations may be best for identifying challenges and brainstorming feasible solutions. They're also best for explaining progress and next steps to clients.

- "Working software is the primary measure of progress." Showing results and products is the easiest way to demonstrate that you're addressing the needs you've identified, even if your way of doing so looks different than initially expected.

- "Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely." Establishing consistent workflows in which team members know how much work they should expect to put into a project is part and parcel of agile project management. With these workflows in place, team members won't become overwhelmed and will be able to properly move a project forward.

- "Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility." Agile project management is iterative, not long-term. As such, team members may find it easier to consistently focus on quality, not quantity. This means fewer mistakes to fix later and thus higher agility in completing projects.

- "Simplicity – the art of maximizing the amount of work not done – is essential." Agile project management seeks to maximize efficiency and limit the number of massive changes that need to be made after a project is supposed to be finished.

- "The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams." Your team should decide for itself how to best divide work and meet the client's needs.

- "At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly." The iterative process, while partially intended to avoid massive last-moment changes, can never be perfect. That's why teams should regularly review their processes and figure out how to improve on them moving forward.

What is the agile project management process?

There are two primary models for the agile project management process: Scrum and Kanban. While there are differences between the two, their approaches comprise roughly the same six primary steps:

1. Project plans

Just as in traditional project management, you should at least set some basic frameworks – problems to be solved, possible solutions – before getting started. If you're using Scrum methodology, the Scrum master will lead the team in mapping this path.

2. Project maps

The map planned in the previous step should comprise each deliverable to be worked toward during an iteration. In both the Scrum and Kanban methods, these steps should be defined, but only in Scrum should a firm timeline be set. In Kanban, you can instead use a Kanban board to manage your team's workload. Other project management tools will likely come in handy for mapping as well.

3. Deliverable dates

In this step, you can turn to your Scrum board to establish firm timelines for completing each iteration, or you can use your Kanban board to get a rough sense of how long each task might take. A Gantt chart, which provides a visual representation of a project schedule, may also prove helpful.

4. Division of labor

With your path and deadlines in place, assign work to each member of your team. Simplicity is essential, so you should evenly distribute the workload among your entire team. Visual workflow representations may help you achieve this goal.

5. Regular updates

To achieve the final of the 12 agile principles, commit to daily meetings in which team members state what they've achieved and what's next for them. Keep these meetings brief in accordance with the simplicity principle, but not so short that team members have no valuable information.

6. Client interaction

In the final stage of agile project management, the client joins. You unveil your iteration's deliverable to the client and determine how to implement any requested changes. You will also discuss workflow improvements and achievements to determine how you can improve your process on the next go-round.

Benefits of agile project management

These are some of the benefits of transitioning your company to agile project management:

- Less uncertainty. Agile project management originated in the software industry because developers often identify a need and then gradually figure out how the solution will look. The iterations and regular feedback of APM allow development teams to efficiently reshape their products to better suit the identified need. This results in a final product that requires fewer changes than it might have with traditional project management approaches.

- Higher-quality products. With improvements and client feedback at every step of the way (instead of it all coming at the end), your products will be better suited to address the problems you initially identified.

- Stronger collaboration. The six steps outlined in the agile management process make for improved, more frequent collaboration between not just your team members, but your company and its clients too.

- Fewer wasted resources. The simplicity principle of agile project management manifests as fewer employee hours spent working on a project, and your employees' time is among your most important resources. So is money – and with more consistent client feedback, you'll encounter fewer instances of spending more money to fix mistakes you could have avoided in the first place.

At the end of the day, agile project management benefits everyone involved, both in and outside your company.

https://bit.ly/34CSF4D