Lean Six Sigma is a proven project management methodology that empowers organizations to reduce costs, increase productivity and create more value for customers—in any industry or job function.

Lean Six Sigma trains teams to improve processes. Lean Six Sigma can be applied to any industry or job function because all businesses have processes. It’s used by our clients in the Fortune 500, Government, Nonprofits and Small- and Medium-Sized businesses.

What is Lean Six Sigma?

Before diving into details, it’s important to clarify the concept of process improvement. Since Lean Six Sigma is a system for analyzing and improving processes we’ll break down those terms first.

What is a Process?

A process is a series of steps involved in building a product or delivering a service. Almost everything we do is a process—tying our shoes, baking a cake, treating a cancer patient, or manufacturing a cell phone.

What is Process Improvement?

Process improvement requires employees to better understand the current state of how a process functions in order to remove the barriers to serving customers. Since each product or service is the result of a process, gaining the skills required to remove waste, rework or inefficiency is critical for the growth of an organization.

Working On a Process vs In a Process

Employees are hired based on their expertise in a given field. Bakers are good at baking and surgeons are good at performing surgery. Professionals are experts at working in a process, but they are not necessarily experts at working on a process. Learning to work on and improve processes requires experience and education in Continuous Improvement. That’s where Lean Six Sigma comes in.

What is Lean?

Lean methodology has been labeled a process improvement toolkit, a philosophy and a mindset. It originated in the 1940s. At its core, Lean is a popular approach to streamlining both manufacturing and transactional processes by eliminating waste and optimizing flow while continuing to deliver value to customers.

What is Six Sigma?

Six Sigma is a process improvement strategy that improves Output quality by reducing Defects. It originated in the 1980s. Six Sigma is named after a statistical concept where a process only produces 3.4 defects per million opportunities (DPMO). Six Sigma can therefore be also thought of as a goal, where processes not only encounter less defects, but do so consistently (low variability).

Combining Lean and Six Sigma Into Lean Six Sigma

Although Lean and Six Sigma have been taught as separate methods for many years, the line has blurred and it’s now common to see Lean and Six Sigma teachings combined together as Lean Six Sigma in order to reap the best of both worlds.

Lean Six Sigma provides a systematic approach and a combined toolkit to help employees build their problem-solving muscles. Both Lean and Six Sigma are based on the Scientific Method and together they support organizations looking to build a problem-solving culture. This means that “finding a better way” becomes a daily habit.

Understanding both approaches and accompanying toolkits is extremely valuable when solving problems. It doesn’t matter where a tool comes from—Lean or Six Sigma—as long as it does the job. By combining these methods you have the best shot at applying the right mindset, tactics and tools to solve the problem.

The Steps of Lean Six Sigma

Lean Six Sigma uses a 5-step method to improve processes and solve problems called DMAIC.

- Define Phase: Define the problem

- Measure Phase: Quantify the problem

- Analyze Phase: Identify the cause of the problem

- Improve Phase: Solve the root cause and verify improvement

- Control Phase: Maintain the gains and pursue perfection

What Are the Benefits of Using Lean Six Sigma?

Organizations face rising costs and new challenges every day. Lean Six Sigma provides a competitive advantage in the following ways:

- Streamlining processes results in Improved customer experience and increased loyalty

- Developing more efficient process flows drives higher bottom-line results

- Switching from defect detection to defect prevention reduces costs and removes waste

- Standardizing processes leads to organizational “nimbleness” and the ability to pivot to everyday challenges

- Decreasing lead times increases capacity and profitability

- Engaging employees in the effort improves morale and accelerates people development

Organizational Development and Lean Six Sigma

Organizational Development (OD) is the application of the behavioral sciences to the resolution of organizational problems. Organizations achieve success through the integrated functioning of people, processes and technology.

Organizational Development practitioners understand that in order to support organizational change it is crucial to understand how the systems and processes of the organization are driven by complex factors such as behaviors and cultural norms.

Lean Six Sigma offers competitive advantages as a complement to Organizational Development, particularly when business transformation requires improvement of operational processes.

Motorola and GE are recognized for their successful implementation of Lean Six Sigma. What is often not highlighted is that both companies’ change initiatives started generating incredible business results when they married Lean Six Sigma with Organizational Development techniques. These organization’s and others since have found that driving change, and business results, comes from integrating the Lean Six Sigma toolbox with the broad and effective methods of Organizational Development.

Who Benefits From Using It?

The Business & Their Customers

Lean Six Sigma works for any size organization. The same success achieved by large businesses can be attained by small and medium businesses. Smaller organizations may actually be more nimble with fewer people and lower levels of red tape to navigate.

This method works for businesses looking for a roadmap to effectively meet their strategic goals. Applying it helps to increase revenue and reduce costs, while freeing up resources to add value where the organization needs them most. The ultimate winners are the customers of the business who receive consistent, reliable products and services.

The Employees

Lean Six Sigma not only improves profit margins, it positively affects employees by engaging them in the work of improving their own processes. Since employees are closest to the actual work of an organization—the delivery of products and services—their intimate knowledge makes them the best resources to analyze and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of those processes.

By participating in successful Lean Six Sigma efforts, employees build confidence and become increasingly valuable assets to the business. Studies show that employees who feel they’re able to positively impact an organization will perform better, be more accountable and live happier lives. By quickly mastering basic Lean Six Sigma skills, they will continually standardize work, root out problems and remove waste in an organization.

DMAIC – The 5 Phases of Lean Six Sigma

Before Starting DMAIC: Select a Good Project

The focus of any process improvement effort is selecting the right project. Good candidates for improvement will set you up for success with DMAIC. Here are 4 key guidelines:

- Choose an obvious problem within an existing process

- Choose something that would make a difference but would not be overly complex to address—Meaningful but Manageable

- Make sure there is potential to reduce lead time or defects while resulting in cost savings or improved productivity

- Check if you can collect data about the selected process—you want to achieve Measurable improvement

Once you’ve selected a good project, you and your improvement team can apply DMAIC to dig into process issues and deliver quantifiable, sustainable results.

Now, on to the DMAIC process!

Define

Define the Problem by Developing a “Problem Statement”

Focus on a meaningful but manageable problem that impacts the customer

Sometimes the hardest part about being a problem-solver is choosing which problem to fix without jumping to a solution. Teams usually begin by “fixing what bugs them” but ultimately the best projects focus on improving customer satisfaction.

Confirm the problem is a priority and will have a substantial impact

Having established a problem, the team creates a Problem Statement which includes:

- A Main Process Measure: Use a measure that impacts the customer of the process. Customers have two process-related “buckets” of concern: Lead Time and Quality. Lead Time reflects the length of time from request to delivery of a product or service. Quality can be many things; accuracy, completeness, number of defects, etc. Simply ask: Are you trying to make the process flow faster? Or are you trying to make the product or service better?

- The Severity of the Issue: It’s key to answer the question, “How big is the problem?” This could reflect things like the percentage of units with errors or the number of late orders per month. It’s important to be specific in order to provide perspective on the issue. Severity data may not be available right away which means the team fills in the blanks later during the Measure Phase.

Confirm resources are available

An important first step is to assign a project team lead, also known as a Green Belt or Black Belt, as well as someone in a leadership position, referred to as a Sponsor or Project Champion. Team members can come from different areas of the organization but should all have some connection to the project area. Are there people close to the process who can spend time working on the issue? Is there someone in a leadership position who would like to see the issue resolved? It is critical to involve people that work in the process.

Define the Goal by Developing a “Goal Statement”

The Goal Statement should be a direct reflection of the Problem Statement. For example, if orders are 10% late, then the goal might be to cut that down to 5% late. This statement defines, in measurable, time-bound terms, exactly when the team and project will be considered successful. Of course, this can be adjusted once the root causes are determined during the Analyze Phase.

Tools: Project Charter

What is a Project Charter?

The Project Charter is a living document that outlines a process improvement project for both the team as well as leadership. Teams use the charter to clarify the process issue being addressed, the reason for addressing it and what “success” looks like for those working on it. It’s also used to clarify what’s not being addressed. It is the first step in a Lean Six Sigma project, and therefore takes place in the Define Phase of DMAIC. The Project Charter is periodically reviewed and refined throughout the project.

The elements of a Project Charter generally include the:

- Problem Statement

- Business Case

- Goal Statement

- Timeline

- Scope

- Team Members

Project Charter Resources

Define the Process by Developing Process Maps

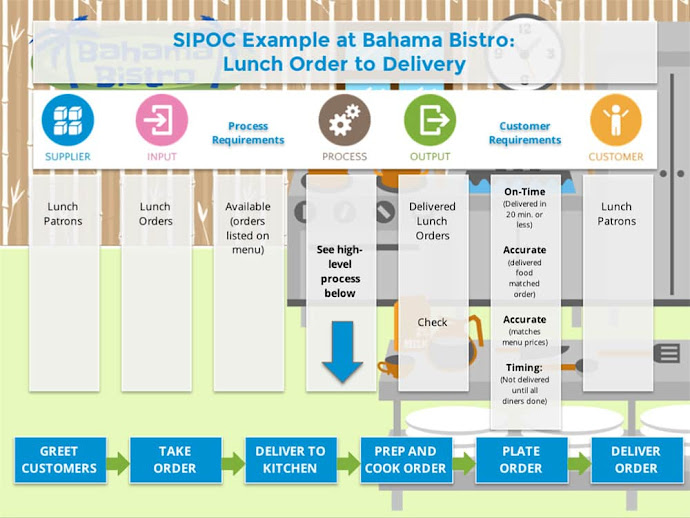

The team establishes the a bird’s-eye view of the processwith a high-level process map. A typical high-level map is the SIPOC which stands for Suppliers, Inputs, Process, Outputs and Customers. Another high-level map, more closely aligned with cycle time reduction projects, is the Value Stream Map. Either of these maps can be used throughout the life of the project.

Once the high-level map is completed, a great way to understand the process in more detail is to conduct a Process Walk, also known as a “Gemba Walk.” During this walk, the project team conducts a series of interviews with process participants to get a full picture of the actual work done at each step. This information helps the team to build a detailed map. Detailed mapping can be done with a Swimlane Map format—which uses lanes representing departments—or it can be depicted with a simple flow-chart.

Tools: SIPOC, Value Stream Map and Swimlane Map

SIPOC

What is a SIPOC Diagram?

A SIPOC diagram is a high-level view of a process which stands for Suppliers, Inputs, Process, Outputs, and Customers. Every Process starts with Suppliers who provide Inputs to the Process which results in an Output that is delivered to Customers.

Benefits of a SIPOC Diagram

By creating a SIPOC diagram, you effectively kick-off your process improvement project with a standard definition of the process to be improved. This way, you can rest assured that your team members move forward with perfect alignment. A SIPOC diagram can then be used as a launchpad for creating a detailed process map, which occurs during the Define Phase of the DMAIC strategy. Having a well-defined SIPOC diagram sets your team up for success at the beginning of your Lean Six Sigma process improvement project.

SIPOC Resources

SIPOC Example

Value Stream Map

What is a Value Stream Map?

A Value Stream Map (VSM) visually displays the flow of steps, delays and information required to deliver a product or service to the customer. Value Stream Mapping allows analysis of the Current State Map in terms of identifying barriers to flow and waste, calculating Total Lead Time and Process Time and understanding Work-In-Process, Changeover Time, and Percent Complete & Accurate for each step.

Swimlane Map (aka Deployment Map or Cross-Functional Chart)

What is a Swimlane Map?

A Swimlane Map is a process map that separates process into lanes that represent different functions, departments or individuals. The process map is called a “swimlane” because the map resembles a pool with lanes identifying the different process groups.

6 Process Maps You Should Know & How to Choose the Right One

A process map is an important part of any Lean Six Sigma project – it helps communicate the process at the center of your project and guides you to specific areas of focus. There are a number of choices available, and choosing the right map helps to clarify your efforts.

The wrong map might confuse matters or simply waste your time. I’ll share key aspects of the following map types:

- SIPOC (and SIPOC-R)

- High Level Map

- Detailed Map

- Swimlane Map

- Relationship Map

- Value Stream Map

The intent is to help you make a useful choice, but not go into how to build each map. If you Google each map name you’ll find examples and guides for constructing them and there are links to helpful templates for some of them. Keep in mind that there are plenty of opinions on the “right” way to make them – find what works for you.

Map #1: SIPOC

SIPOC is an acronym for Supplier – Inputs – Process – Outputs – Customer, and may not be considered a true process map by a purist. I like to think of it as a “one box” process map. That might not seem like much of a map, but it establishes the basis for subsequent mapping.

The importance of the SIPOC is that it shows, in very simple terms, what the process accomplishes while identifying the key players. The center contains the a few high-level process steps. The required inputs (and their providers) are listed to the left, and the key process outputs (and their recipients) are listed to the right. The SIPOC provides a focus for discussion of what the process is all about.

The importance of the SIPOC is that it shows, in very simple terms, what the process accomplishes while identifying the key players.

In this case we are examining the purchasing process in which a requester submits a purchase requisition that details what’s to be purchased. The requisition is received and a purchase order is issued to a supplier, who subsequently delivers what was ordered. The SIPOC also can define the scope of the project: in this case, the process of converting a request into an order placed with the supplier. It does not include the actual delivery, the invoicing or the payment. The SIPOC would have different outputs or customers if the project had a broader scope.

I recommend creating a SIPOC for every project because they are helpful when discussing the process with others and they’re incredibly simple to make! Your first SIPOC may feel a bit awkward, but with a little practice you can make a SIPOC for nearly any process in less than five minutes.

The SIPOC discussed here is the simplest form – there have been many improvements, including the SIPOC-R (discussed next), and the GoLeanSixSigma version, which actually combines the SIPOC with a high level process map (see https://goleansixsigma.com/sipoc/).

SIPOC-R

The SIPOC-R is a variation on the SIPOC in which the requirements (or specifications) for the inputs and outputs are listed, typically just under each input or output. In this case, a proper requisition might include the item description, date needed, an account number to charge, and an authorizing signature. Often the additional detail provided by requirements offers clues to problems we might wish to solve. If the problem exists even though all of the input requirements have been satisfied, then the cause is either in the process itself or in a missing (unstated) requirement. On the other hand, if the requirement has not been met, we should investigate the causes and you may not need to delve into the process details.

If we need to examine the process, we want to make sure we see how the process converts the SIPOC inputs into the outputs, so the SIPOC can help us avoid missing some important relationships.

Map #2: High Level Process Map

High Level Process Maps show how the process works in just a few steps. The purpose is to provide quick and easy insights into what the process does, without getting into the details of how it’s done. This can be useful when communicating to leadership and others who have no need (or interest) in seeing the details.

High Level Maps typically don’t require a deep knowledge of the process, so you can often construct them with the assistance of managers. Think of the High Level Map as simply an expansion of the center “process” from the SIPOC into five to ten more detailed boxes. This map shows where all the inputs go, and where all the outputs are created.

High Level Maps typically don’t require a deep knowledge of the process, so you can often construct them with the assistance of managers.

In this case, each function or department is shown in a different color. This isn’t essential, but it’s useful. In most projects a High Level Process Map is adequate to describe the process. As you investigate underlying problems, you can put marks next to the steps (dot’s, x’s, stars) when you find problems originating in that step. When complete, it forms a visual concentration diagram, showing where the problems lie in the process.

Map #3: Detailed Process Map

We don’t normally need to see the entire process in detail, but there may be some parts of the process that require a Detailed Process Map. This is especially true if there are a number of problems with that step. In this example, we might be interested in exploring the Purchasing step. We simply consider the input to that step, identify what immediately happens with that input and then repeatedly ask the “what happens next?” question until we produce the output. If this provides the necessary level of detail, we can stop here. If, however, we need to know more about the “Get three quotes” part of the process, we could explode it into more detail. The key is selectively diving into the detail. It’s a lot of work to create a detailed process map – you need to talk to the people who work the process in order to find out what really happens – managers often don’t know the process at this level of detail. I prefer to start with a High Level Map and let the needs of the project dictate when to go into more detail and how far to dive down.

The exception is if we intend to radically streamline the process. In that case we have to get close to the “work instruction” level of detail in order to isolate the few nuggets of the process that are truly value-added.

The exception is if we intend to radically streamline the process.

Finding value-added activities in a process cannot be done in a High Level Process Map. In fact, if the value-added activity is evenly distributed throughout the process, then at a high level, all of the steps will appear to be value-added because they all contain an activity that contributes value. If you blow up each step into its detail you will find that the true value-added activity is isolated in one or two small steps.

Map #4: Swimlane Map

This Swimlane Map is especially helpful when establishing work instructions and training for the new process because it makes each participant’s role explicit.

This style of process map is highly valued because it clearly shows “who does what,” when they do it and an arrow crossing a lane indicates, a handoff. For this reason, Swimlane Maps are favored by managers who who appreciate additional information. The drawback is that Swimlane Maps are not space efficient, especially if there are multiple lanes with few steps. In such maps some lanes are nearly empty which means the overall process map takes up more space. In addition, processes with a lot of handoffs can be awkward to depict in a Swimlane Map since they result in many arrows crossing multiple lanes. My preference is to use traditional, high level and detailed maps during the project work, and use the Swimlane Maps for the improved process since it will be simpler with fewer boxes, participants and handoffs. This Swimlane Map is especially helpful when establishing work instructions and training for the new process because it makes each participant’s role explicit.

Map #5: Relationship Map

Relationship Maps are technically not process maps since they don’t detail the work done, but they do show the participants and how materials, paper or information flows between them. This map was popularized by Rummler-Brache, and is not widely used, but I wanted to share it as an option. This map is useful when initially exploring the process, typically at a high level, to determine the identity of participants.

If there are only a couple of participants in the process there is no point in creating a Relationship Map, but if there are many participants it is a helpful addition to a High Level Process Map. Once you have created a Relationship Map, you can use it to complete your process map by confirming that the arrows in the Relationship Map originate from the steps creating the unit and end in the proper place.

Map #6: Value Stream Map

Value Stream Maps are typically used in Lean applications where we are interested in either showing pull scheduling or opportunities to do pull scheduling. They are often detailed and difficult to read. However, they are rich with information that is useful when planning process improvements. Value Stream Maps are often used when planning a Lean implementation to display the current state of the process including material flows, information flows and other information important for Lean implementations.

A few distinguishing features:

- Material moves from left to right

- Information which triggers release of materials or scheduling of production moves from right to left

- Work-in-Process (WIP) is shown in the triangles

- Relevant process details such as cycle time, changeover time, etc. are shown below each process step

- Wait time and work time appear on a line at the bottom of the map

- Improvement opportunities appear as starbursts

They require more skill to build than simpler process maps, but they provide great information.

Value Stream Maps are sometimes called Material and Information Flow Diagrams. They require more skill to build than simpler process maps, but they provide great information. For this process, the diagram shows there is essentially neither pull nor flow, a little over a day’s worth of work-in-process inventory and lots of wait time. The process should produce one part every 18 minutes (takt time) to meet the customer demand, but four of the five process steps cannot meet this output pace. It takes 6.56 days for a part to get through the process (though it’s needed in 5 days), after receiving 108 minutes of work. An experienced Lean practitioner will quickly see a lot of opportunity here!

Choosing the Right Map

It may seem that I am advocating the Value Stream Map, but I am not. For Lean implementations it is helpful, but for routine problem solving it may be substantial overkill. So how do we choose the right map for the job? The following chart provides guidance:

Many projects make use of several maps types. You might start out with a SIPOC, followed by a High Level Map. After some investigation you might decide to make a detailed map of selective portions of the areas where problems exist. After finding root causes and creating a revised process, the Swimlane Map can provide helpful documentation.

Use the maps to tell a story or to make reality visible to you – let the needs of the project dictate the map you choose!

One last point – conduct a Process Walk whenever possible. It’s a great way to learn the process and confirm that what you’ve been told is real and not just a good story.

Bill Eureka

Process Walk (aka Gemba Walk)

What is a Process Walk?

A Process Walk (Gemba Walk) is an informational tour of the area where the work is taking place. A Process Walk is a series of structured, on-site interviews with representative process participants with the goal of gaining a comprehensive understanding of the process. Interviews focus on detail such as process time, wait time, defect rates, root causes and other information that can lead to targeted improvements.

Process Walk Resources

5 Reasons You Should Go to the Gemba + 6 Tips to Get You Started

“Gemba” is a Japanese word that translates into “the site” or “the place of work.” There is a related word, “Gembutsu” which means the “actual thing.” We “go to the Gemba” to find out what is really happening.

That might be a nice piece of philosophy, but what does it have to do with improvement? As facilitators of improvement, we often have problems to solve, and need to quickly assess the facts of the situation in our search for root causes. For those of you familiar with the Process Walk – it is one type of Gemba, but depending upon the problem you may not need to walk the entire process – or you might have to walk several of them.

Fact vs. Fiction

As problem solvers, we often have much more information than we need and must sift through it all to find not only the relevant information, but to separate fact from fiction. When we begin our quest to solve a problem, we will often talk to knowledgeable people to get background on the situation. Sadly, it is amazingly common for those people to give us information that may be misleading or simply untrue.

If they truly understood what was causing the problem, chances are that your help wouldn’t be needed.

I’m not suggesting any malicious intent, but rather that the people you talk to may be blinded by “honest wrong beliefs.” If they truly understood what was causing the problem, chances are that your help wouldn’t be needed. There are often unique attributes to the situation that may defy an easy solution by those close to the process.

As an independent problem solver, you can bring two essential qualities: objectivity and ignorance. You can be objective only if you are not corrupted by the honest but wrong beliefs of those close to the process. As an “outsider” to the process, your initial ignorance gives you a “blank slate” that may allow you to see past the “honest wrong beliefs.”

Reason 1: There’s No Substitution for Observing the Process in Person

I was working with a company who made earthmoving equipment. I helped them implement Six Sigma by coaching some of their Black Belt candidates. I was approached by a candidate for a second opinion – he didn’t like the advice he received from his assigned coach. The Black Belt candidate was stationed at the home office, while the problem was in a remote plant, reachable only after an arduous journey. In addition, he was newly married and would rather spend evenings with his wife at home than in a remote motel. He advocated conducting the project entirely by conference call, avoiding the plant visit. Now I’ve been at this for quite awhile, but I still remember what it is like to be a newly-wed; still, I advised him to go to the plant and see for himself.

He was trying to remedy an extremely serious problem: the plant was shipping half their orders late! The plant manufactured hydraulic fittings and was causing delays at other plants. The candidate thought it was a terrible project because he would have to deal with a lot of “poor performers”, but I assured him that he was very fortunate to have such a great first project. Why? The problem was so bad that someone’s job was in danger, so there would be great desire to fix the problem. Besides, performance was so bad that the problem was likely to improve all by itself.

Once we got past these preliminaries, I advised him to go to the plant, observe the operations and test the information he had been given. The leading reason claimed for the late shipments was that there were a number of urgent orders that required shipment in less than standard lead times. My disappointed, newly-wed traveled to the plant and quickly discovered that there were indeed urgent orders, but they accounted for less than 10% of the late shipments. This meant that most of the late shipments were the result of something else.

My disappointed, newly-wed traveled to the plant and quickly discovered that there were indeed urgent orders, but they accounted for less than 10% of the late shipments

I won’t get into the entire diagnostic journey, but the Black Belt candidate discovered by being there that most of the late shipments were the result of actions taken at the plant, inadvertently causing the very problem they were trying to solve. I won’t claim that going to the Gemba was what solved the problem, but it certainly helped.

If you are reluctant to go to the Gemba I urge you to reconsider. You might have been told quite a story by the insiders, but the Gemba will allow you to see for yourself what is happening. Even a beginning problem solver can learn much by simple observation.

Reason 2: Bust Every Assumption

In another instance, I was called into a plant to solve a capacity problem. I listened patiently while they explained that the “Cold Presses” were the constraint, and that lately Scheduling had been giving them small loads to produce, which wasted capacity and slowed the process. After a time I had heard enough, and asked to see the Cold Presses. I was taken to the shop where I saw eight Cold Presses, half of which were idle. I asked why these critical resources were not working, and was told they would be operating soon. After half an hour, loads moved in and out of the presses, but most of the time half were idle. My associates tried to explain that this was unusual. I asked them to track how many loads they produced on each machine for the next day.

We all realized that the Cold Presses were not the constraint, and we proceeded to discover the real constraint and fix the capacity problem.

The following day the data showed that none of the Cold Presses produced as much as they should have. After some discussion, we all realized that the Cold Presses were not the constraint, and we proceeded to discover the real constraint and fix the capacity problem.

Reason 3: Discover the Real Deal

On another occasion I encountered suspiciously “round” numbers. While attempting to streamline a process we encountered an operation which was to run for 30 minutes – a suspiciously round number! When I asked the origin of the 30 minute standard I was first told that it was part of the work instructions, but further digging led to a process engineer who had specified the time. In discussion with the engineer we discovered that the value was determined through “engineering judgment.” Now, if you are not an engineer, engineering judgment sounds rather mysterious, but it’s really just a guess – made by an engineer!

This wasn’t a big improvement, but a six minute savings over thousands of loads a year adds up!

The engineer agreed to some tests and we discovered that the minimum time required to produce a quality result was 22 minutes. We agreed to change the standard to 24 minutes to provide a margin of safety. This wasn’t a big improvement, but a six minute savings over thousands of loads a year adds up!

Reason 4: Simplify the Complexity!

Business can be complicated, unless you force it to be simple.Think about how you would run the process if you were doing it in your garage.

I was asked to work with a shipping manager to resolve a truck loading problem. The plant had four dock doors and had long been requesting additional dock doors. When you drive by a major warehouse or distribution center there are often 50-100 dock doors evident, so four seems like a very small number.

After half an hour of briefing in conference room I suggested that we go to the loading dock. At the dock I saw two trailers pulled into two of the four dock doors, with the other two being empty. There was a small staging area filled with boxes. The loading dock was at the end of the production area and many of the products coming off the line went right into the trailers, while some were set off to the side. When I asked why, I was told that those boxes were for a different customer.

As I watched, I thought that if I were running this operation out of my garage I would want all the product to go right from the production line to the trailer, and then on to the customer. I asked what determined the order product came off the line, and was told it was based on the order in which they were started. After a little discussion we determined that if we scheduled all the product for a certain customer to together, it would come off the line together and could go right onto the trailer. After further discussion with production management we conducted a few trials and soon discovered that four dock doors was more than enough!

Reason 5: Opportunities to Ask

Don’t be afraid to ask what might seem ridiculous – you could be on the right track!

I was working with a service operation for earthmoving equipment. Machines were brought into the shop for repairs. In many ways it was similar to an automobile repair operation at a car dealer. The problem we were attacking was invoice generation, which typically took ten days or more – sometimes several months. The client felt that ten days was an acceptable time, but wanted to reduce the really long times. When an invoice reached a customer several months after the service, the service may not even have been remembered, which led to challenging the invoice, and often negotiating a lower price settlement.

I was struck by how similar the operation was to automobile service and asked the client how long it took them to get an invoice when they brought their car in for service. They smiled and said they not only got the invoice the same day, but had to pay for the service before taking the car!

They were quick to point out that “this is not an auto repair operation – we give our customers 30 days to pay.”

They were quick to point out that “this is not an auto repair operation – we give our customers 30 days to pay.” Even so, why delay giving them the invoice? As a result, they substantially streamlined the process. They never got down to same day invoicing, but they reduced the time to far less than ten days, and nearly eliminated the really late invoices!

6 Tips for Going to Gemba

- Dress for the location – if you are going to the shop floor or a warehouse, dress casually. One of my associates ruined a new pair of dress pants when an adhesive applicator squirted on him

- Keep an open mind and learn – nobody should expect that you know much about the problem – you are there to discover what is not yet known

- Ask lots of questions – if the answers don’t make sense to you, keep asking!

- Ask to see examples of what you have already been told – one solid piece of evidence is worth more than lots of stories

- Question “round” numbers, or numbers that seem to convenient – they may be based on judgments rather than facts

- If you can envision what an “ideal process” might look like, explore what about the “as is”real process is different – if you know of a similar process that runs better, use that as a reference.

Okay, so you’ve decided to go to the Gemba – how much is enough? Unless it is impossible, I suggest that you always go at least in the beginning, and if practical visit from time to time to stay in tune. Believe me, nothing can compare to your actually seeing for yourself!

So, where and when will your next Gemba Walk be?