Небольшая по объему, но любопытная книжка издательства Альпина Паблишер:

Дарья Денисова, журнал «Эксперт»

Порядок, столь ненавистный большинству в детстве, со временем превращается для многих в идеал бытия, часто недостижимый. Не знаю как вас, а меня в признанном «парке культуры и отдыха» жителей крупных городов, сиречь магазине IKEA, завораживают макеты меблированных типовых квартир в натуральную величину — так ладно у них там все организовано. Даже грешным делом подумаешь: пришел бы кто-нибудь ко мне, ненужное отобрал и выбросил, нужное рассортировал и разложил так, чтобы было удобно пользоваться.

Шаг 1. Информация на визитке, в подписи к электронным письмам

Основные элементы визитки (рис. 1) и электронной подписи (рис. 2). Порядок следования номеров па визитке сообщает звонящему о ваших ожиданиях. В современной бизнес-среде при отсутствии e-mail визитка теряет смысл. Визитка должна быть лаконичной с информационной точки зрения

Рис. 1. Основные элементы визитки

Рис. 2. Подпись к электронному письму

О размере компании и корпоративном стиле немало расскажет адрес электронной почты. Сравните:

masha@company.ru

marya@company.ru

Ivanova.Marya@company.ru

Ivanova.MV@company.ru

masha@company.ru

marya@company.ru

Ivanova.Marya@company.ru

Ivanova.MV@company.ru

Шаг 2. Имена файлов/папок, темы писем

Некоторые принципы категоризации файлов:

- Суть документа в имени файла

- Дата в названии файла

- Сокращение, аббревиатуры и другие маркеры в названии файла

Среднестатистичекий человек способен одновременно удерживать в своей кратковременной памяти 7 ± 2 параметра.

Удобство графы «Тема письма» заключается в том, что она позволяет, не раскрывая самого письма, узнать по существу его содержание. Можно провести аналогии между темой письма и именем файла. И то и другое существенно облегчает поиск и навигацию по базе файлов или писем.

Шаг 3. Ваш информационный фонд

Грамотная регистрация информации создает предпосылки для удобной и быстрой навигации по вашим информационным фондам. Информации много не бывает. Десять раз подумайте, прежде чем занести палец над клавишей Delete. В любой рабочей папке имеет смысл завести поддиректорию под названием «Архив» и складывать в нее все, что мешает в папке основной, но когда-нибудь может понадобиться. …прямо в файле заведите некое подобие журнала событий — «шапку» параметров файла. Подход, при котором в теле файла содержится полная информация о его параметрах и особенностях, крайне необходим, если материал находится в коллективном, а не индивидуальном использовании.

Практикуйте метод ограниченного хаоса — любую информацию, с которой пока не понятно, что делать, не удаляйте, а складывайте во временное хранилище. Информация может повредиться, поэтому ее желательно бэкапить (создавать резервные копии). Еще одна зона «ненадежности» — сетевые документы в глобальной сети. Часто бывает, что страница с важной информацией вдруг перестает существовать по тому адресу, который был сохранен в папке «Избранное» вашего интернет-браузера. Именно поэтому наиболее важные страницы можно и нужно сохранять на собственном жестком диске в виде html-документов (или импортировать в документы другого формата).

Храните весь свой электронный информационный фонд в отдельной папке компьютера (например, в каталоге WORK). Тогда при смене очередного ноутбука или жесткого диска вам не понадобится тратить время и нервы на копирование разрозненных папок. Постарайтесь разобраться, где на вашем ПК хранятся папки, в которые Интернет-браузер складывает ссылки, cookies и тому подобное. Разместите эти папки также в рабочем каталоге, переписав адресные строки в программах.

Любую информационную работу необходимо базировать на триаде регистрация – навигация – анализ (информации). Порядок в информационных фондах наводят при помощи архивирования информации, а для перестраховки от сбоев (технических и других) применяют регулярное резервное копирование информации. Две эти процедуры необходимо наладить для любого информационного массива — от книги контактов в мобильном телефоне до объемной базы данных на рабочем компьютере. Чтобы повысить комфортность обращения с вашими информационными фондами, необходимо, по возможности, «развязать» информацию и технические средства — сделать информационные фонды мобильными. Соберите всю важную информацию в определенных местах, не рассредоточивая ее по рабочим папкам разных программ. Тогда и апгрейд техники будет проходить менее болезненно, и комплексное резервное копирование займет меньше времени.

Шаг 4. Коммуникации с другими информационными работниками

Как не существует в природе механизмов со стопроцентным КПД, так и в любом общении (межличностном и тем более групповом) невозможно стопроцентное взаимопонимание. И как физики, оттолкнувшись от этого факта, начали разработку более эффективных энергосберегающих двигателей, так и информационные работники однажды задумались над тем, как избежать потерь в процессе коммуникации. Под транзакционными издержками в менеджменте понимают затраты на проведение любого основного действия (транзакции).

Для информационного работника транзакциониые издержки – это потери на коммуникациях. За этим определением может скрываться:

- непонимание информации / поручений / приказов и т.д. (причем вы сами можете не понять суть поступившего распоряжения, и точно так же непонятым может остаться ваше поручение);

- недопонимание;

- невольная неверная трактовка;

- сознательная неверная трактовка, если формат информации/приказов и так далее позволяет такие действия;

- недостаточное внимание к информации/приказам;

- нарушение сроков и других условий.

При коммуникациях необходима система подтверждений. Введите в свою информационную жизнь систему запросов (например, по ICQ или mail), что-то типа: «хотел бы обсудить то-то и то-то… Когда удобно?». Для важных переговоров, выступлений и т.п. создаем систему регистрации информации (секретарь, видио- или аудиозапись). Продолжением регистрации информации становится система фиксации фактов. Например, после встречи направить письмо типа: «договорились о следующем… Нет замечаний?».

Принцип трех гвоздей.

При ведении электронной деловой переписки надо стараться с помощью несложных приемов делать эту коммуникацию более четкой и удобной: использовать графу «Тема письма», сохранять историю переписки в теле письма, грамотно выстраивать диалог (цитировать фрагменты, разбивать вопросы на пункты с присвоением им номеров и т.д.). Делайте контрольную вычитку письма, которая занимает не более 5% времени, требуемого на его написание.

Шаг 5. Оценка и экспертиза информационных продуктов

Иногда нам встречаются слабые документы. Чтобы иметь возможность объяснить и себе, и другим, что же не так с изучаемым документом, нам понадобятся какие-то точки отсчета. Ниже мы разберем простой, но эффективный инструмент качественной оценки информационных продуктов. Для этого запомним аббревиатуру ФТОП — она складывается из первых букв слов при перечислении следующих качеств информационного продукта:

Ф — форма представления информации;

Т — точность информации;

О — оперативность информации;

П — полнота информации.

Ф — форма представления информации;

Т — точность информации;

О — оперативность информации;

П — полнота информации.

С приходом электронного документооборота каждый информационный работник должен приучить себя мыслить именно в цифровом, а не аналоговом формате. Авторский лист – 40 000 знаков, страница А4 – 2500 знаков (12-й кегль, полуторный междустрочный интервал).

…фотография размером 1000 X 1500 пикселей в формате jpg «весит» от 0,5 до 1 Мб (в зависимости от типа фотографии и степени сжатия). А формат, сохраняющий максимум качества (не сжимающий картинку в ущерб качеству), — tiff — для такого объема требует порядка 4,5 Мб (на один пиксель здесь нужно три байта для хранения информации о цвете — по байту на каждый из базовых цветов RGB). Таким образом, цифровое фото приучает нас мыслить в пикселях (а также в мегабайтах).

Завершающей стадией создания любого информационного продукта должны быть его экспертиза. Предпочтительно – внешняя.

Шаг 6. Повышение емкости информационных продуктов

Современный бизнес-сектор вполне осознает проблему дефицита времени: учебники по тайм-менеджменту стоят в рейтингах бизнес-литературы на первых местах. Дефицит внимания — он же ограниченность психофизиологического ресурса человека — пока еще осознан не так широко. Но борьба за этот ресурс уже ведется сегодня на передовой информационного общества.

Лучший способ оптимизации текста – это создание в нем четкой структуры. Если вы точно знаете, о чем должно быть письмо, но никак не можете вылить свое знание «на бумагу», напишите в девственно чистом электронном документе четыре вопроса: Что? Для чего? Благодаря чему? Что еще известно? Теперь под этими вопросами фиксируйте те факты, которые собирались изложить. Когда добавить к написанному будет уже нечего, сотрите вопросы и изучите получившийся текст.

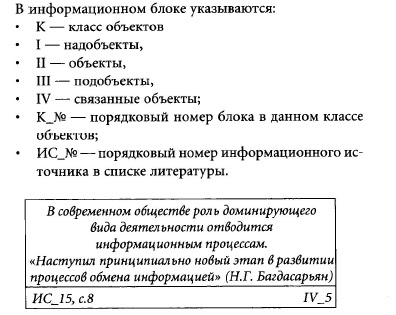

Описанный подход — предельно упрощенная реализация научного метода информационной работы. Называется он «метод объектно-документального анализа (МОДА). Метод опирается на принципы объектного программирования, и четырем упомянутым вопросам соответствуют Надобъекты (ответ на вопрос «Для чего?»), Объекты («Что?»), Подобъекты («Благодаря чему?») и Связанные объекты («Что еще известно?»). Так возникает аббревиатура HOПС, а действия по приведению информационных продуктов к такой структуре называются НОПС-форматированием.

Альтернативный подход основан на использовании Принципа пирамиды Минто.

Рис. 3. Пример информационного блока

Вообще говоря информация не линейна, а многомерна (наилучшим образом с такой сущностью справляется гипертекст). Именно в нелинейном виде информации хранится в наших головах. С другой стороны, восприятие информации повышается, если ее подавать в виде многокомпонентного продукта: текст, аудио-, видео-, графика, иллюстрации. Говорят, что прямой путь к правополушарному (ассоциативному, творческому) мышлению лежит через дополнение сухого рационального текста живыми и эмоциональными медиакомпонентами.

Интеллектуальный фильтр – набор критериев и правил, которые мы применяем, когда из неудобного и объемного информационного массива создаем компактный и легко воспринимаемый информационный продукт (сравните с тем как описывает Джозеф О’Коннор преломление явлений / событий реального мира через наши ментальные модели).

Шаг 7. Источники информации

Критерием, позволяющим проводить разделение деловой информации на значимую и несущественную, служит ее новизна. Чем сильнее полученный информационный прирост влияет (в положительную сторону) на вашу деловую жизнь, тем полезнее эта информация. Даже если она влияет опосредовано — например, меняя мировоззрение. Выбирайте информационные источники с возможностью архивирования данных.

Используйте несколько источников информации. Используйте принцип двух дивизионов. Например, ваш выбор газет может быть таким:

- первый дивизион — «Ведомости», «КоммерсантЪ» (для ежедневного чтения)

- второй дивизион — «Газета», «Известия», «РБК-Daily», «Независимая газета», «Российская газета» (для периодического чтения).

Изучение печатной периодики – не только средство доставки актуальной информации, но и инструмент объединения делового сообщества, средство его саморефлексии. (В Интернете таковыми можно считать «сообщество менеджеров e-xecutive» или, например, Профессионалы.ru.)

Использование платных источников информации – информационный аутсорсинг. Вы могли бы собрать информацию и сами, но эффективнее и, скорее всего, выгоднее – поручить работу профессионалам. Некоторые платные базы данных: СПАРК Интерфакс, Интегрум, Медиалогия, TNS.

Шаг 8. Книги как источник информации

По данным «Левада-центра», сегодня только 24% россиян читают книги, и от лидирующих по этому показателю англичан (52%) мы отстаем более чем два раза. …утешаться нам – чтецам – приходится лишь тем, что такая ситуация дает ощутимые конкурентные преимущества каждому четвертому россиянину (т.е. россиянину читающему).

Основным критерием качества книг остается полезная новизна. …можно разделить все новые и полезные знания на те. которые необходимы вам уже сейчас (актуальные), и те, которые могут пригодиться в обозримом будущем (перспективные).

Книгу хочется оценить еще до ее покупки. Именно поэтому современные издания снабжаются аннотациями и краткими рецензиями на обложках или во вступлении. Обращайте внимание на декларации автора и издательства: на какого читателя рассчитана книга, чего в ней больше — теоретики или практических методой? Просмотрите информацию об авторе: почему именно он написал книгу именно па эту тему, каков его багаж знаний и практического опыта? Загляните в библиографию, если она есть, — это позволит оценить бэкграунд книги, научный или практический. Естественно, изучите оглавление. Если после всего этого интерес к изданию еще не пропал, откройте его произвольно где-нибудь в середине и прочитайте пару абзацев – оцените стиль и слог. Наконец, выберите по оглавлению раздел, посвященный теме, в которой вы разбираетесь лучше всего, просмотрите пару страниц и попытайтесь оценить профессионализм автора, исходя из ваших знаний. Как показывает практика, именно после этого последнего шага часто приходится отказываться от покупки. Составлять броские аннотации уже научилось большинство авторов и издательств — маркетинг делает свое дело, а вот качество контента нередко оставляет желать лучшего.

При чтении нужно отмечать важные фрагменты, чтобы не забыть о них и не тратить в дальнейшем по десять минут на их поиски. Размечайте и индексируйте книги и любые печатные материалы — тогда повторный поиск заинтересовавшей вас информации не будет занимать много времени и чтение станет более эффективным.

Чтобы создать предпосылки для разнообразного чтения, необходимо предоставить себе право выбора. Поэтому не ругайте себя, когда понимаете, что читаете далеко не все, что покупаете, и многое откладываете с мыслью «надо посмотреть». По опыту многих активно читающих людей, для эффективного самообразования необходимо покупать в три-пять раз больше литературы, чем будет в итоге прочитано.

Шаг 9. Профессиональный рост

Мы развиваемся только тогда, когда нас подвигают к этому окружающие условия. Создавать такие условия – наша личная обязанность. Сила творческого тока (скорость профессионального развития – I) прямо пропорциональна желанию развиваться – D, и разности потенциалов (профессиональных, творческих – U):

I = U * D

Чтобы создать разность потенциалов нужно:

- попасть в соответствующую корпоративную среду (профессиональную) и / или

- общаться со знатоками своего дела (экспертами).

Перед началом любых преобразований необходимо оценить текущее положение дел. Осознание своих сильных и слабых сторон позволяет эффективно использовать первые и устранять вторые. Способов оцепить себя существует множество – от простейших психологических или профессиональных тестов до процедур ассесмент-центра или найма профессиональных индивидуальных тренеров. Нелишним будет проводить подобный аудит регулярно, а результаты аттестаций фиксировать и архивировать, чтобы периодически оценивать рост достижений.

Ничто так не способствует росту, как контакт с профессионалами – мастерами своего дела. Работа в организациях с высокой корпоративной культурой или постоянные контакты с экспертами создают предпосылки для профессионального развития. Выявить «правильные» организации информационному работнику помогут такие признаки, как присутствие в компании четких стандартов в области обмена информацией или наличие системы управления знаниями. Организовать прямые или косвенные контакты с экспертами помотают отраслевые коммуникационные площадки (семинары, выставки, образовательные программы) и медиа-активность соответствующих специалистов — их присутствие в информационном пространстве через общеделовые или профессиональные СМИ.

Шаг 10. Карьерные стратегии информационного работника

Стивен Кови, автор концепции Р / (Р + С) (подробно изложена в книге «Семь навыков высокоэффективных людей»), советует не забывать о том, что достижение любого результата «Р» [в числителе] всегда нужно соотносить с восполнением и расширением собственных ресурсов и средств («Р + С»). В вашем плане развития «Р + С» должно быть уделено не меньше внимания, чем просто «Р» (результату).

Игорь Манн в своей книге «Маркетинг на 100%. Ремикс» предлагает заняться самомаркетингом и для этого представить себя в виде товара — продукта, продвигаемого на рынок вакансий (или рынок профессиональных услуг). Иногда бывает весьма полезно описать свою карьеру как жизненный цикл продукта, изучить, в чем заключается уникальность вашего предложения и что создает вам (как «продукту») конкурентные преимущества и даже основания для временной монополии.

Глеб Архангельский в книге «Тайм-драйв. Как успевать жить и работать» рекомендует изобразить на линейном графике (шкале времени) свою планируемую жизнь, отметив ожидаемые периоды и задачи (обучение, воспитание детей, выход на пенсию). Соотнеся диаграмму своей жизни с такими же графиками ваших родственников (или партнеров по бизнесу), можно заранее предсказать напряженные жизненные периоды и сложные моменты, что-либо скорректировать и подготовиться к предстоящим процессам.

Список рекомендованной литературы

- Нордстрем. Бизнес в тиле фанк

- Борд. Нетократия

- Питерс. Представьте себе!

- Друкер. Задачи менеджмента в XXI веке

- Йенсен. Общество мечты

- Горкина. Пять шагов от менеджера до PR-директора

- Карр. Блеск и нищета информационных технологий

- Мариничева. Управление знаниями на 100%

- Кляйн. No logo. Люди против брендов

- Коноплев. INFO-драйвер