As a young marketer navigating the digital landscape, I love frameworks. Not only do they help me plan and prioritize, but they help me visualize how everything I’m working on fits together.

No, I won’t be talking about (and I’m looking at you, classically trained marketers) the 4Ps, Porter’s 5 forces, or SWOT analyses. Sure, those frameworks have their place, but they don’t provide much direction for startups looking to focus their energy on growth. Plus, they’re getting pretty old.

The frameworks below were developed by modern marketing gurus. Together, they’ll help you make a growth strategy, select traction channels, and influence your customers’ behavior.

Growth Frameworks

Let’s start off with some growth frameworks. These models will help you determine how to grow, when to grow, and what metrics you should be tracking.

The Startup Pyramid

Sean Ellis (CEO of Qualaroo, godfather of growth hacking) uses this framework when thinking about startup growth. This one is great because it gives you a rough game plan depending on what stage your business is in. The pyramid is comprised of three stages:

- Product/Market Fit: Appropriately at the base of the pyramid, the first and most fundamental part of the model is achieving product/market fit. The idea behind this is that you should never waste resources on growing something that people don’t want. If you go down that path, you’ll just die trying.

- Transition to Growth: Once you know you have something people want, it’s time to transition to growth. This part of the model involves understanding what makes your product valuable to people and how you can get more people to experience this value. More specifically, you’re setting yourself up for success in the next phase by maximizing your conversion rate.

- Growth: Now you’re finally ready to put the gas on some growth channels and bring on the traffic. This stage begins with testing channels and analyzing their performance. After that, you’ll want to optimize and double-down on the high performers. As for selecting channels in the first place, I’ll dive into some other frameworks that will help us with that later.

Pirate Metrics: “AARRR!”

Dave McClure (Founder of 500 Startups) developed Pirate Metrics to guide startups on their quest to acquire and convert customers. I love this framework because it’s easy to see how a user might go through this funnel, and it shows you where your metrics are suffering the most.

Let’s take a look at the basics:

- Acquisition: How do users find you in the first place? Think of your growth channels. This could be from paid search, a Facebook ad, a piece of content, etc.

- Activation: Did users actually do anything once they landed on your site? While user activation will be defined differently for each business, this could be as simple as signing up for an account, to something more involved like completing a profile.

- Retention: Do users come back? Here you’ll have to define what it means for a user to be inactive. For your business, this could mean a user that hasn’t made a purchase in a two-month period. Calculate your churn rate and, as a starting point, make sure it’s at a good level for your industry.

- Revenue: How do you make money? Of course, all of this is pretty pointless if you don’t have a way to make money. Here you can look at metrics like customer lifetime value(LTV), conversion rate and shopping cart size.

- Referral: Do users tell others about your product? If they do, you’re benefitting from some degree of virality. This magnifies the effect of any of your acquisition efforts, and is particularly useful if you engage in paid acquisition. It effectively lowers your customer acquisition cost (CAC) because every user obtained brings on more users themselves.

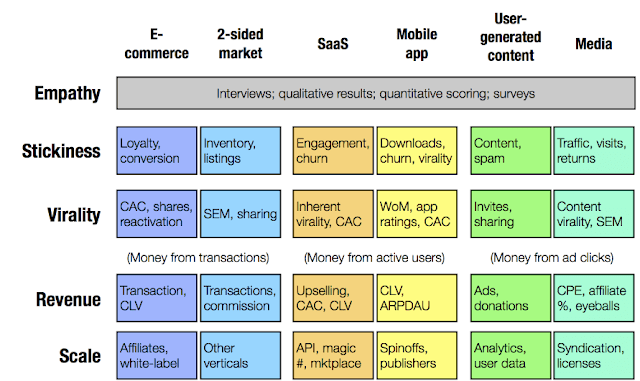

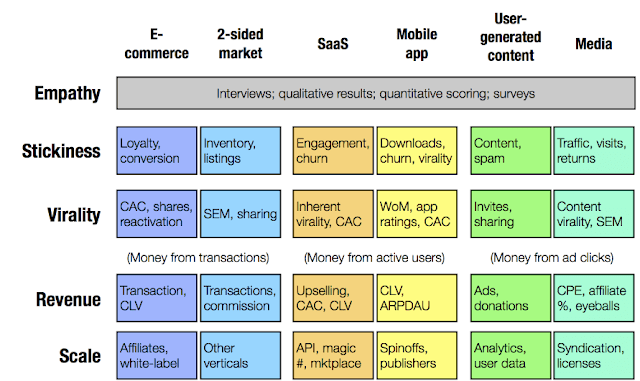

Lean Analytics Stages

In their book Lean Analytics, Alistair Croll and Ben Yoskovitz present their own framework called Lean Analytics Stages. Their model combines elements from a number of different frameworks, including the two above. In their view, startup growth is best broken down into five key stages:

- Empathy: The purpose of this stage is to inform the development of your minimum viable product (MVP). The metrics at this stage are mostly qualitative, since you’re empathizing with your customers and listening to their feedback. You’re ready for the next stage when you’ve identified a problem that you know you can solve profitably in a sizeable market.

- Stickiness: Now you need to build something that keeps people coming back. Engagement and retention are the focus here as you iterate your MVP to optimize these metrics. You’re ready for the next stage once you’ve got an engaged user base and a low churn rate.

- Virality: Before throwing money into advertising, you’ll want to maximize the growth you get from existing customers. As I mentioned before, virality helps you get more out of your marketing dollar. Once you’re seeing a good amount of organic growth, you’re ready for the next stage.

- Revenue: Once again, you’ve gotta make some money. On top of that, you need revenue coming in to fuel customer acquisition efforts. This is where you’ll be tweaking your business model to prove you can make money in a scalable way. CAC and LTV are important metrics here as you ensure customers bring in more money than they cost to acquire. When you’ve reached your revenue and margins goals, you’re ready to scale this thing.

- Scale: As a company that now knows its product and market very well, efforts will now be focused on making more money from your current market and/or entering new markets.

Channel Selection Frameworks

With so many possibilities and a million things to do, it’s hard to decide where to put your marketing efforts. These frameworks will help you find your killer acquisition channels.

The ICE Score

Here’s Sean Ellis with another dose of genius — the ICE score. I love this one because it’s a quick and dirty way to evaluate potential growth channels. All you have to do is ask yourself three questions:

- What will the impact be if this works?

- How confident am I that this will work?

- How much time/money/effort is required?

Let’s put this in context. When Airbnb first came up with the idea to integrate with Craigslist, the potential impact was undeniable. If this worked, they’d tap into Craigslist’s massive user base. They were confident in the idea, since they had team members that could pull it off, and no user would say no to more traffic on their listings. However, this plan would require a fair amount of effort from their team to get the integration up and running. Ultimately, Airbnb went for it due to the potential impact and their confidence in the idea — and it definitely paid off!

There’s two ICE frameworks. This one helps you prioritize what to test first by: measuring the impact of the test (impact), confidence level in the test working (confidence), and how easy the test is to implement (ease).

There’s two ICE frameworks. This one helps you prioritize what to test first by: measuring the impact of the test (impact), confidence level in the test working (confidence), and how easy the test is to implement (ease).

The second ICE framework helps you prioritize by: measuring growth and company benefits (impact), determining the cost of implementing (cost), and understanding the amount of resources required to test (effort).

The Bullseye Framework

The Bullseye Framework, developed by Gabriel Weinberg and Justin Mares for their bookTraction: A Startup Guide to Getting Customers, gives us a more in-depth model for channel selection. Their five step framework breaks down the process of finding the one channel you should focus on (bullseye!):

- Brainstorm: Naturally, you’ll have biases towards certain traction channels. To avoid missed opportunities, they suggest thinking of at least one idea for each of the 19 traction channels. I won’t list those here, but Traction covers all of them in detail!

- Rank: This step has you thinking critically about your mountain of ideas. The goal is to categorize ideas as either high potential, possibilities, or long-shots.

- Prioritize: Now you want to re-think your categories once again, carefully selecting your top three high potential channels.

- Test: With your three ‘high potentials’, you can now devise cheap tests to gauge feasibility. The goal here is to find which one of these channels is worth your undivided attention.

- Focus: Armed with your test results, start directing resources towards your most promising channel. You’ll want to squeeze every bit of growth out of this channel by continually optimizing results through experimentation.

Behavioral Frameworks

To close out this list, let’s take a look at two frameworks you can use to influence user behavior. You’ll notice these tie in nicely with key growth concepts we talked about earlier — stickiness and virality.

The Hook Model

User psychology guru Nir Eyal presents the Hook Model in his recent book, Hooked: How to Build Habit Forming Products. He suggests that the products we use regularly work their way into our lives by cultivating habitual user behavior. He also believes that these habit forming products follow a similar iterative cycle:

- Trigger: Bringing a user into the cycle starts with a trigger. At first these will be in the form of external triggers such as push notifications, but as the cycle repeats they will convert into internal triggers that will continue to drive the user forward. Since negative emotions are often internal triggers, one example would be a pang of loneliness followed by the urge to jump onto Facebook.

- Action: The easier it is to do something, the more users will do it. Habit forming products make action easy.

- Variable reward: To create a habit, it’s necessary to reward the action that was triggered. However, research shows that humans are motivated by the anticipation of a reward. By adding variability into the reward system, you increase anticipation. Think about the sweet sweet anticipation that you might have a notification waiting for you on Facebook.

- Investment: Finally, to solidify the habit, users need to invest themselves in your product. On Facebook we build a network of friends, and on Instagram we have collection of photos. These investments make it hard to leave.

STEPPS

Jonah Berger, author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On and creator of STEPPS, says it best: “Virality isn’t luck. It’s not magic. And it’s not random. There’s a science behind why people talk and share. A recipe. A formula, even.” Luckily, you can use this formula to create your own contagious content:

- Social currency: People care about how they are perceived by others. Use this to your advantage, and people won’t be able to resist talking about you. Invite-only web apps harness this by making users feel like insiders.

- Triggers: If people are frequently reminded of your product, they’ll talk about it more. Jonah notes the example of Rebecca Black’s song “Friday” having a huge spike in plays on — when else? — Fridays.

- Emotion: Content is more likely to go viral if it is highly emotional. The type of emotion matters too — something that evokes anger (a high arousal emotion) is more likely to be shared than something that evokes sadness (a low arousal emotion).

- Public: The more public something is, the more likely people will talk about it. Think about the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge: the creators were able to take something that was normally private (donating to charity) and make it very public. Genius.

- Practical value: People like to share things that are useful. Make high value content and they’ll pass it on. Like this article for instance!

- Stories: People like to tell stories. Jonah describes stories as your Trojan Horse—build compelling narratives, and they’ll carry your idea along for the ride.

While this is just a quick overview of some of my favorite modern marketing frameworks, you probably have an idea of how each one might apply to you. I’d recommend diving deeper into each one and thinking about how you can apply them to your business.

Lloyd Alexander is a recent marketing grad who’s excited about technology and digital marketing.

Источник:

Источник: